CGj interviews Dr Robert Wright, Associate Professor, Department of Management and Marketing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, author of a recent report that provides insights from psychology on how to approach complex challenges.

Highlights

- many of the challenges we face in our lives require us to step out of our comfort zone

- finding creative solutions to problems not encountered before often requires us to let go of past approaches and assumptions

- when good problem solvers find themselves stuck, they may need to reframe the problem – problem setting is just as (if not more) important as problem solving

Thanks for giving us this interview. Your latest research report – CEO Report – interviews senior executives about their problem-solving strategies. Can we start with why you chose as the subtitle of the report: ‘the psychology of the unknown’?

‘The human condition is that we are very comfortable with things that are familiar. I taught MBA students – typically middle managers with on average 15 years of work experience – for quite a few years. I asked them what type of problem they like to solve and almost unanimously they replied “the problems that we can solve”.

That is a big giveaway – they were reluctant to engage with problems that they felt were beyond their ability to solve. “We prefer to solve problems that we’re good at,” they would say. Many of the challenges we face in our lives, however, require us to step out into the unknown and when faced with such challenges we need to be prepared to step out of our comfort zone.

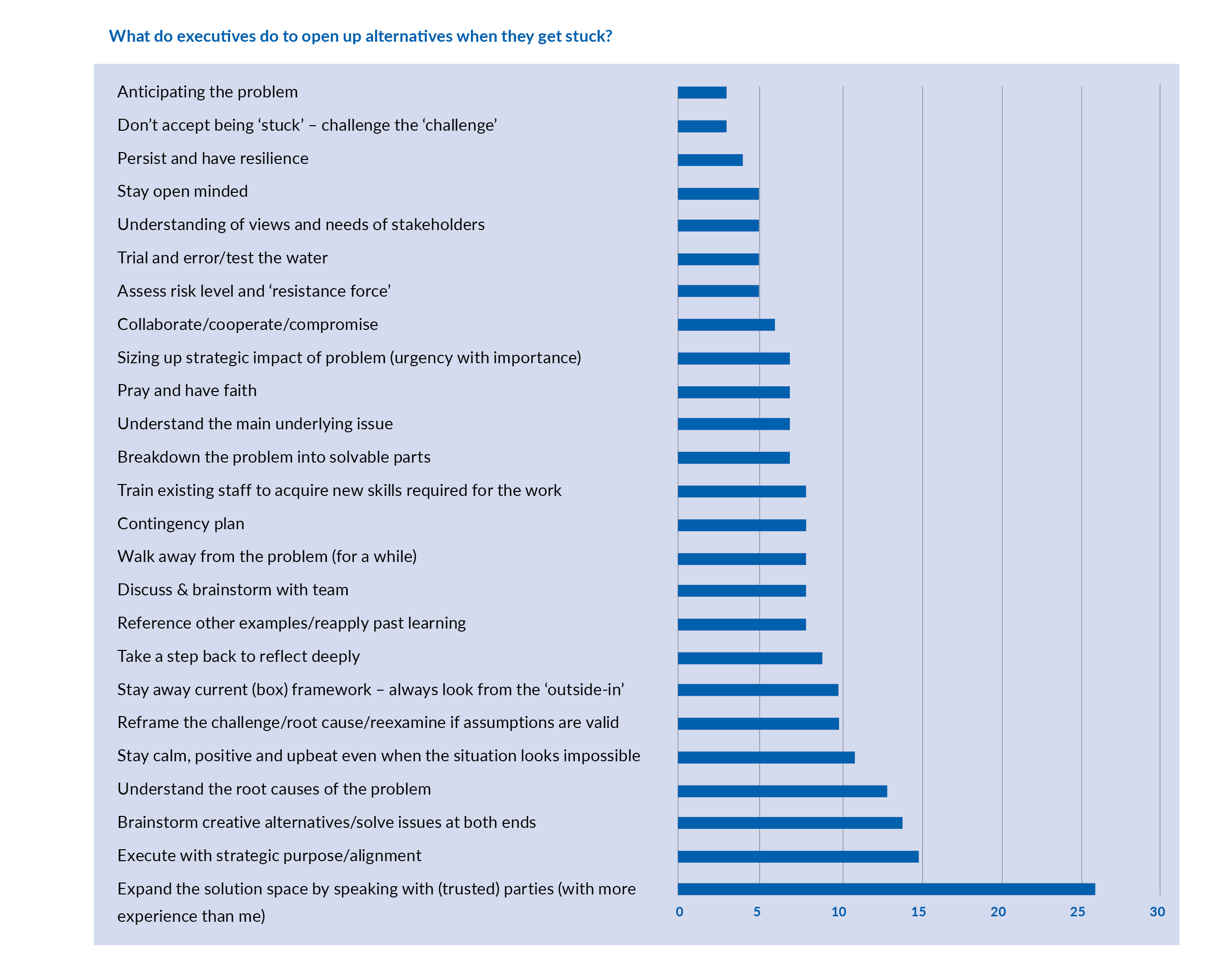

The CEO Report is based on interviews with 50 senior executives from a wide range of sectors. We asked them to describe situations where they found themselves stuck when trying to solve a problem and what they did, or failed to do, in order to progress. The problems they described were various, but our focus was on what they did, or failed to do, when they found themselves stuck. Based on their responses, the report highlights seven habits of mind that can help when trying to solve complex challenges.’

Before we get into that, could you explain the Repertory Grid Technique (RGT) you used in your interviews for the report?

‘To cut a long story short, George Kelly, a clinical psychologist, developed this interview technique in the late 1920s/early 1930s. He recognised that we think in contrasts. We compare and contrast things that are similar or different – that is how we make sense of the world. So he came up with an ingenious way of eliciting how people think about an issue by asking them to consider three elements of the topic under discussion and to identify ways in which two of the elements might be seen as alike and distinct from the third.

So in our case we would ask our interviewees for three situations where they got stuck when trying to solve a problem. We then posed the question – in what way are any two of these similar, but different from the third?’

Do you think psychology has useful insights for directors and senior managers? I ask because there is often a resistance among board members and senior executives to get involved in discussions about psychology.

‘Executives often say they don’t have time for psychology, particularly now as businesses are still trying to catch up on lost time, lost profits and lost customers after the pandemic. But maybe we need to frame it differently. For example, I don’t know if you’ve heard of the “invisible gorilla test”. The subjects of this experiment were asked to watch a video of people passing basketballs and to count the number of passes made. Meanwhile, someone in a gorilla suit walks in and out of the scene. About half of the subjects were so focused on the task of counting the passes that they failed to see the gorilla. The term for this is “inattentional blindness” and it has important implications for executives.’

Could we turn to the seven habits of mind you mentioned earlier that your report highlights for building good problem-solving skills?

‘I use the acronym “focused” for these seven habits of mind.

The first letter F is for fresh perspective. This is about seeing things differently. When good problem solvers find themselves stuck, they may need to reframe the problem. I think there needs to be more emphasis in executive development on the power of reframing. We often feel that once things have been defined they are cast in stone, but things change and we need to adapt and keep on reinventing ourselves. If we stick to the old definition of what it takes to succeed, we will never succeed in the “tomorrowland”.

The second letter O is for taking full ownership of the problem. This is about taking the approach that this is my problem so what am I going to do about it?

The third letter is C for connected thinking. When confronted with the unknown, great problem solvers begin by starting to connect the dots. This often means connecting ideas from in and outside the domain you are in. Sometimes the best ideas come from outside so it pays to look for ideas from other sectors and other walks of life.

The fourth letter is U for urgency with end in mind. We found many of the interviewees were able to progress because they had a timeline and an agenda to push for a solution. That way they were more focused on getting out of the unknown. Another thing they did under the umbrella of having a sense of urgency was that they were able to let go of past approaches and assumptions when they were obviously not helping. I think that is a powerful revelation on how to progress, and not just for executives but for all of us. As Lao Tzu said: “To seek knowledge, collect something every day. To seek the Way, let go of something every day.”

The fifth letter is S for leveraging off teamwork – team spirit. Good problem solving is about teaming up to benefit from collective intelligence. When great problem solvers get stuck, they ask themselves – who’s got the most expertise here? If you have deference for expertise, not just within teams but between teams, you enter a different ballgame and that allows you to progress.

The sixth letter is E for really getting “in the zone” – being engaged with the problem. Having a close engagement with the problem means testing hypotheses. Good problem solvers are like scientists, they are always experimenting with new ideas. This helps them to find where the pain points are – where the first domino is going to fall.

The final letter is D is really about “reflective/reflexive practice” – or exercising deliberate practice. This means taking a step back and asking what we are doing now and what we should not be doing. Are we even measuring the right things? What are the critical factors for success? What does success look like?’

It sounds like problem solving is a more creative process than we perhaps imagine – do you think this has implications for how far artificial intelligence (AI) can be used to solve problems?

‘AI is the future and we don’t know today just how much more it can do. I’m sure it can do much more than it’s currently doing, but we must not lose sight of the fact that we as humans have to remain independent. How can I frame this? If we let a calculator help us all the time, we will soon have to depend on the calculator for something as simple as five plus five. What a travesty that would be if we allowed that to happen. So yes of course we should embrace AI, but at the same time we must go back to fundamentals and ensure that we as humans don’t lose sight of who we are and our capacity to flourish. I think that is a bigger calling.’

You mentioned the importance of looking for creative solutions that might come from outside the domain you are in – do you think that is another incentive for organisations to broaden the diversity of their workforce? A thought leadership paper published by The Chartered Governance Institute in 2021, for example, highlighted the benefits of bringing ‘diversity of thought’ to boardrooms.

‘Yes. I think diversity goes beyond the gender issue and I like where you are going with the reference to “diversity of thought”. Executive development courses, for example, recognise that if executives are going to solve a problem presented to them in a case study, they are going to need to come at it from all angles. So they will often form learning teams composed of people from all over the world. They know that, to really understand the complexity of the situation, all great teams need to have a diverse geography of thought.’

Finally, what would you say are the key takeaways from your CEO Report?

‘What I hope executives will take away from this report is that problem setting is just as (if not more) important as problem solving. Moreover, executives need to learn to respond rather than to react when they find themselves stuck. When people find themselves in quicksand, what do they do? They struggle to get out, but their movements only sink them deeper. I hope, rather than react to challenges, they can respond with the seven habits of mind highlighted in the report.’

Dr Wright was interviewed by CGj Editor Kieran Colvert. For further information about the report discussed in this article – CEO Report: The Psychology of the Unknown – please contact the author at: robert.wright@polyu.edu.hk.

“many of the challenges we face in our lives… require us to step out into the unknown”