Discreet tips for company secretaries on resolving boardroom conflicts.

Directors like to think of themselves as entirely rational agents of the company's interests and not at all subject to the emotional and cognitive biases that blight ordinary mortals. The reality, of course, is very different. Directors may be capable of extraordinary feats of teamwork and collaboration, but they are also capable of behaviour that leads, sometimes catastrophically, in less salubrious directions. This month, CSj gives some discreet tips on how company secretaries can assist the chairman in dealing with personal conflicts in the boardroom.

Margaret Thatcher, the UK's infamously autocratic prime minister of the 1980s, goes into a restaurant with her cabinet ministers. The waiter comes to take their orders. 'I’ll have the Beefsteak, rare,’ says the premier. 'And the vegetables?’ the waiter asks. 'They’ll have the same,’ Thatcher replies. This deliciously irreverent sketch from a 1980s UK comedy series has a relevance beyond the world of UK politics. The 'Thatcher's cabinet’ scenario – where a dominant CEO/ chairman is paired with a submissive board – is a relatively common scenario in boardrooms around the world and will no doubt be familiar to some readers of this journal.

Is there anything necessarily wrong with this scenario? A CEO with a strong personality is often, after all, the driving force which makes for a very successful business. While this is true, there are also very obvious risks involved in a situation where the board is not effectively monitoring management nor providing strategic direction. The 'rubber-stamp’ board which fails to challenge a dominant, not to say domineering, CEO/ chairman is in fact just one of a whole range of 'personality issues’ that can jeopardise board effectiveness. The reverse scenario of a weak CEO/ chairman and a combative board can be equally damaging. Then there is the problem of the personality clashes at board meetings and the problem of rival alliances forming among board members.

To address these issues, believes Gregg Li, author, board architect and professor, boards first need to get beyond the taboo surrounding directors’ personalities and the dynamics of their interactions. While it is acceptable to discuss directors in terms of their expertise, experience and ability, issues relating to personality and personal motivation are all too often out of bounds. Where personality issues threaten board cohesiveness and the effectiveness of its decision making, this reluctance to address the root causes of the conflict can be suicidal.

This article will look at why personalities matter on boards and will attempt give some discreet tips to company secretaries on resolving boardroom conflicts. While the primary responsibility for ensuring effective relationships on the board rests with the chairman, the company secretary can play a key role in assisting the chair in this important task.

Every board needs a beast?

There is nothing wrong with strong personalities. Indeed, a recent article by Lucy Kellaway in the Financial Times – 'Everyone benefits from a beast in the boardroom’ – argues that having at least one 'beast’ on your board can be a useful way of preventing directors from getting too cosy. A beast comes in particularly handy where the board has slipped into that semi-conscious, liminal sphere of 'groupthink’. 'They dash in on the attack, battering-ram style, leaving it up to the chairman to restrain them before serious damage is done. Their attack leaves the way open for the nicer, more constructive board members to come in after them, attacking more powerfully than they otherwise would have,’ Kellaway writes.

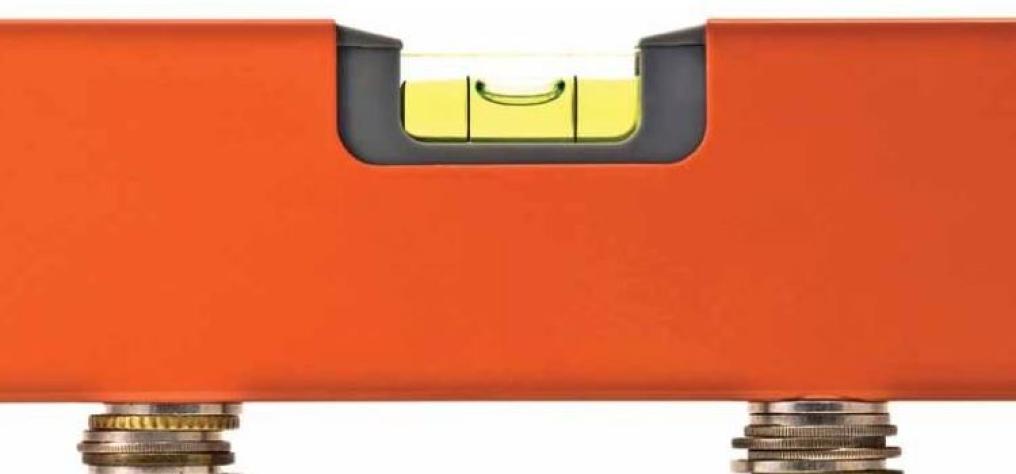

Sounds useful? Keeping boardroom discussions alive is clearly crucial for boards of directors. 'There are boards that are alive and boards that are dead,’ Gregg Li says. 'You want to have some degree of tension but not too much.’ He cites one case he came across where 'the conversation was so mild and genteel that the board appeared to be in a trance-like state. It was simply rubber-stamping whatever was brought by management to the attention of the board and creating a controversy was disdained. There was a constant drone of silence in the room – groupthink was setting in.’

The trouble with the boardroom beast method of keeping discussions lively is that you may end up with discussions becoming a little too lively – directors pounding on the table, items of stationery being thrown. 'There is nothing wrong with having a beast in the boardroom,’ Li says, 'but the beast should be under control.’ The question is, of course, how that can be done and, more pertinently for readers of this journal, what can the company secretary do to help? Should they remain silent and leave it to the chairman to bring the meeting to order? Company secretaries are responsible for ensuring a healthy decision-making environment for the board – this is the ultimate objective of many of their board support functions, such as providing timely and accurate board papers, minute and time-keeping, etc. However, assisting the chairman to ensure the right personal dynamics within the board might seem a rather daunting task to add to those duties.

Respondents to this article, however, agree that the company secretary can and should play a role in ensuring that personality issues do not jeopardise board effectiveness. Susie Cheung, General Counsel and Company Secretary of the Hong Kong Mortgage Corporation, points out that the company secretary needs to keep the focus of the meeting on the real issues at hand. 'Often big arguments can stem from little misunderstandings,’ she says. 'When directors get side-tracked, you need to bring things back to the main issue. I wouldn’t say we play the role of the arbitrator of boardroom disputes, but we are definitely a facilitator of board procedures, responsible for making the whole process more efficient. That is in fact one of the very basic functions of the company secretary.’

She adds that the company secretary's role in preparing for board meetings is also critical here, since he or she can warn the chairman of potential problems before they escalate out of control. Gregg Li agrees and cites another fairly common scenario – where rival alliances have formed on the board – as an example of this. If action is not taken, subsequent debates may find members taking sides not based on the merits of the arguments but on the basis of their loyalties. 'This is the beginning of a divided board,’ says Li. If an alliance becomes a permanent thing and one director is an echo of another, the board needs to consider whether that director is adding anything to board discussions.

Into the lion's mouth

So, daunting though it may be, the company secretary does need to get involved. The company secretary is responsible for maintaining the correct protocol needed for directors to effectively meet and carry out their monitoring and strategic leadership roles. Where that is threatened by personal conflicts, the company secretary needs to work with the chairman to bring the whole endeavour back on track. 'The job of the company secretary is to remind everyone of the function of the meeting and to abide by the rules of the game,’ says Gregg Li. He recommends that simple ground rules are agreed by the whole board when it first meets and that the company secretary be tasked with reminding everyone of them in future meetings. If things get out of hand during a meeting before such ground rules have been set, he recommends the company secretary calls a time-out for the ground rules to be established. 'Calling time-out is a powerful tool that the company secretary must master and not be afraid to use,’ he says.

In many of the problem scenarios explored by this article, board procedural rules take on an added importance. In the scenario of the dominant CEO/ chairman, for example, the company secretary's procedural role provides an important check on the power of that individual. Where a director wishes his objections to be recorded in the minutes, for example, the CEO/ chairman cannot override the legal duty of the company secretary to record that dissent. Timekeeping is another potential flashpoint. If you have a group of directors eager to move board discussions on before objections are raised against their favoured proposals, the company secretary may need to step in to ensure that the issue is fully debated. Or equally, the reverse scenario, where you have delay tactics in a debate, the company secretary may need to call time on the discussion.

The much neglected EQ factor

Board meetings are never going to be an easy process to manage. There are many individuals involved, and, as we have seen, there may be competing agendas involved. Gregg Li believes that the difference between a competent and a really exceptional company secretary often comes down to his or her ability to perceive and respond to the dynamics of the personal interactions going on in the boardroom. 'We can assume that the company secretary will have integrity, will not violate any codes and will be technically competent. Probably 99% of company secretaries will have these qualities, but what makes a really good company secretary is having the sensitivity for the personal dynamics on the board,’ he says. He adds that this sensitivity needs to be backed up with the courage to speak up when a point of view is needed from the company secretary. 'A professional secretary must not be afraid to offer a position on procedural or meeting matters. Over time this will bring respect. This duty also puts pressure on the company secretary to remain at the top of his or her game,’ Li says.

Susie Cheung agrees. 'This is one aspect of the job of the company secretary where you have no help from the rulebook,’ she says. She adds that the humble art of 'tact’ is invaluable in these situations.

‘Choosing the right time to bring something up, using the right tone, and using the right words to get your message across are all critical. There are times, for example, when you first need to listen before trying to get your point across.’ She agrees, however, that company secretaries need to have the courage to speak out when the time is right. The technical knowledge and skills they need to advise directors on regulatory compliance and corporate governance will be wasted if they stay silent for fear of upsetting their colleagues on the board.

‘I think your personal convictions and your professionalism are both very important,’ Ms Cheung says. 'There is no getting away from the need for a good knowledge of the listing rules, etc, but quite often people are afraid to speak out in case they upset somebody. You need to have the courage of your convictions to advise directors. I believe that if you have the long-term interests of the corporation at heart, then you will be less concerned about upsetting this or that director.’

She cites the example of a company secretary advising the board of a bottled water company debating whether to save money by buying cheap, but highly polluting, transport vehicles. 'You would need to point out how this may be regarded by the public, particularly since the company is in the business of selling clean water,’ she says. The trucks may be cheap but companies need to report on their environmental impacts and getting a reputation as a polluter is unlikely to be in the long-term interests of the company.

The responsibility for the final decision, of course, does not rest with the company secretary. Susie Cheung stresses that the company secretary should not therefore be only concerned with 'winning’ the argument. 'At the end of the day, we live in a democratic society and boards abide by the majority decision. If six out of 10 directors vote in one direction, as long as you have communicated effectively the risks involved, you have done your job and you won’t have bad dreams,’ she says.

Gregg Li

Gregg Li has written extensively on board governance issues for CSj, including his highly popular boardroom 'first aid’ course for chairpersons and company secretaries published across six editions (February–July) in 2010. Lucy Kellaway's 'Financial Times’ article 'Everyone benefits from a beast in the boardroom’ was published on 9 October 2011 and is available online.

SIDEBAR: Behavioural governance

Since the 2008 global financial crisis there has been an increasing focus on the issue of directors’ personalities and the balance of relationships on boards. One of the positive spin-offs of the crisis has been a new willingness to look at boardroom issues with the insights that psychology can bring. This has led to the birth of 'behavioural governance'.

A central premise of behavioural governance – that directors’ personalities are just as crucial to board function as more familiar criteria such as their competence and expertise – has become widely accepted globally. In June 2009, for example, the ICSA published a report on Boardroom Behaviours that looked at the way boardroom behaviour is shaped by a number of key factors, including:

- the character and personality of the directors and the dynamics of their interactions

- the balance in the relationship between the key players, especially the chairman and the CEO, the CEO and the board as a whole, and between executive and non-executive directors

- the environment within which board meetings take place, and

- the culture of the boardroom and, more widely, of the company.

The report makes a number of suggestions on how to maintain a healthy decision-making environment on the board, for example via:

- independent thinking

- the questioning of assumptions and established orthodoxy

- challenge which is constructive, confident, principled and proportionate

- rigorous debate • a supportive decision-making environment, and

- a common vision.

The ICSA report also points out that regular board evaluation helps to ensure that any personality problems are identified before they jeopardise board effectiveness. 'High standards of rigorous and, occasionally, independent evaluation are needed to increase boards’ effectiveness,’ the report states.

The ICSA report Boardroom Behaviours is available on the ICSA website: www. icsa.org.uk.