Climate change disclosures – is the world too focused on this topic?

The Best Paper of the Institute’s latest Corporate Governance Paper Competition looks at the issue of climate change disclosure and investigates whether the world is overly focused on this issue, or if it is an overlooked priority.

Highlights

- to ensure sustainable business practices, demand is expanding for companies to disclose climate-related information, including their carbon footprint and the potential impacts of climate change on their operations and prospects

- to align with the ISSB global climate change disclosure standards, Hong Kong’s ESG regime will be tightened for all listed companies

- other important ESG issues such as labour practices, supply chain management, diversity and inclusion, and data privacy

The Institute’s annual Corporate Governance Paper Competition and Presentation Awards has been held since 2006 to promote awareness of corporate governance among local undergraduates. In the first of two parts of this year’s Best Paper, the authors discuss the relevant concepts, explore the current global climate change disclosure regimes and evaluate the view that the world might be too focused on climate change disclosure.

Introduction

‘Of all risks, it is in relation to the environment that the world is most clearly sleepwalking into catastrophe,’ the World Economic Forum warned. Thus, revealing information about climate change, including but not limited to a company’s carbon footprint and the potential impacts of climate change on its operations and prospects, is given increasing weight in the capital market. As such, climate change disclosure is not only used as a government policy to encourage or even mandate companies to regulate their production to minimise environmental impacts, it is also an indicator of sustainable investing. Aside from profitability, environmental concern is becoming one of the dominant factors influencing investment decisions. Under the rising trend of green investing, GSS+ (green, social, sustainability, sustainability-linked and transition) volumes held a 5% share of the global bond market in 2022, implying an expanding demand for climate-related disclosure from companies to ensure sustainable business practices. Yet, this has sparked a debate over whether the world is too focused on climate change disclosure. However, we believe that the world is not too focused on this important issue – as climate risks become more urgent, the world is beginning to give climate change disclosure a proportionate level of attention.

This paper is dedicated to (i) defining the concept of environmental, social and governance (ESG), (ii) exploring current climate change disclosure regimes in a global context, (iii) explaining the factors supporting the view that ‘the world is too focused on climate change disclosure’, (iv) and, if so, stating the challenges the world would face, (v) providing justifications for upholding our stance, and (vi) envisaging the future direction of climate change disclosure. Here, in part one, we focus on the first four of these topics.

ESG

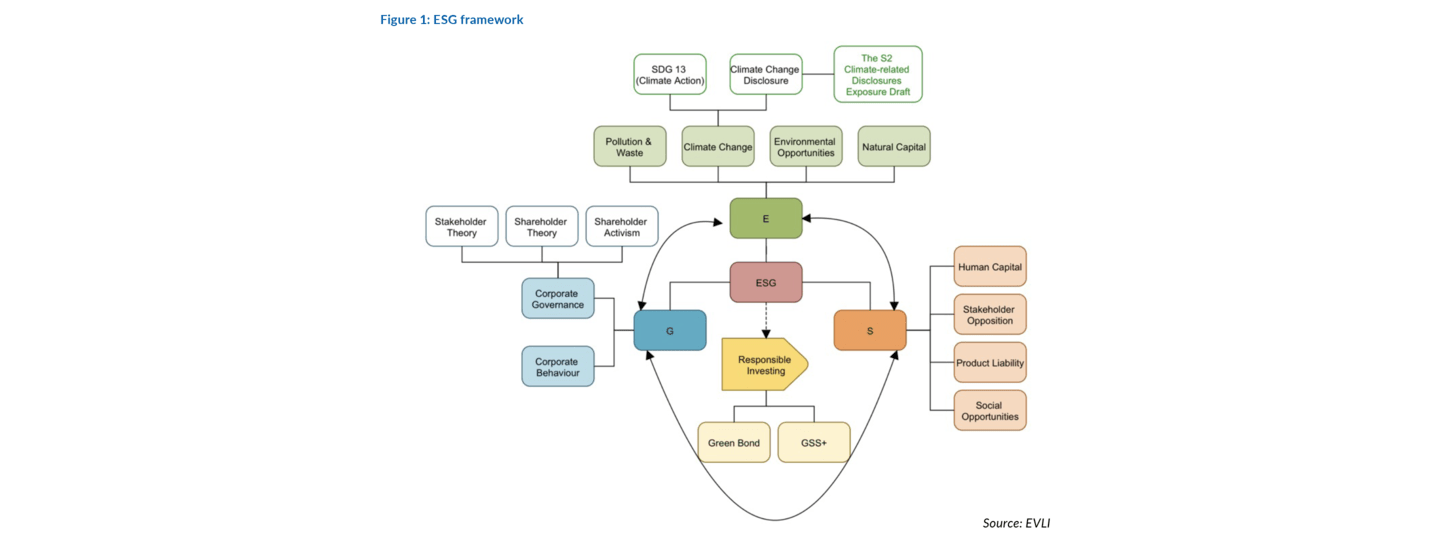

ESG is a non-financial framework using environmental, social and governance factors to assess the sustainability of companies and to measure business risks and opportunities (see Figure 1). Socially responsible investors would usually use ESG performance as a benchmark to screen investments. The following examines the intimate relationship between climate change disclosure and ESG, forming the bedrock of a sustainable economy.

Environmental

The environmental factor examines a company’s environmental impacts and risk management practices, including the company’s overall resiliency against climate risks. Climate change disclosure serves as a tool to assess the environmental factor by publishing the carbon footprint of business activities, the vulnerability of the business activities to climate risks and the company’s plans to combat climate risks. Climate risks are categorised into physical risks and transition risks. The former risk relates to the physical impacts of climate change, while the latter relates to the transition to a lower-carbon economy. With a growing call for climate change disclosure, there are multiple international independent organisations running global disclosure systems, guidelines or standards for companies to manage their environmental impacts. CDP Worldwide, the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board and the Global Reporting Initiative are some examples.

environmental concern is becoming one of the dominant factors influencing investment decisions

Social

This paper focuses on environmental and governance aspects. For completeness, the social factor looks at a company’s relationship with internal and external stakeholders, ranging from employees, suppliers and customers to community members and more.

Governance

Corporate governance looks at a company’s management, for instance, how well it manages capital distribution, the balance of interest between internal and external stakeholders, and compliance with established standards relating to accounting and risks. It is critical to a company’s level of accountability and transparency of leadership. When it comes to prioritising a company’s business and social responsibilities, there has been a longstanding controversy over the merits of shareholder theory versus stakeholder theory. Stakeholder theory is the more accepted theory in today’s world, where climate change disclosure is a gradually more common corporate practice. It suggests that profit maximization is not the sole corporate responsibility – businesses should also have a moral responsibility to consider the interests and well-being of their stakeholders.

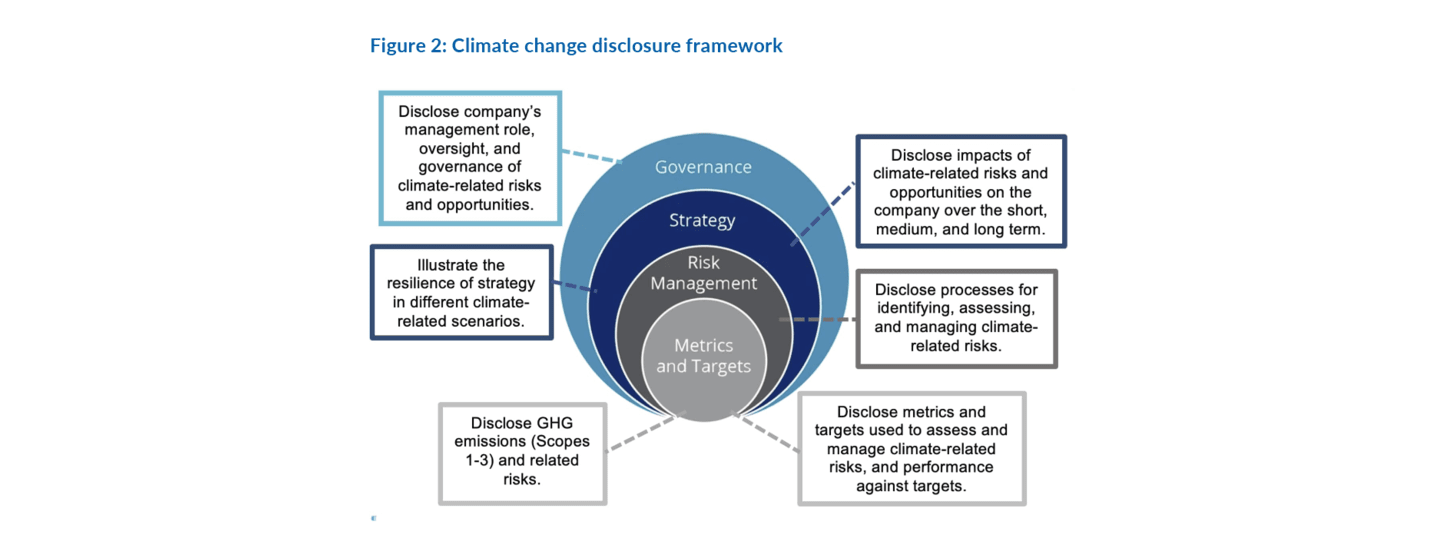

As such, stakeholder theory implies a positive relationship between the extent of responsiveness to the pressure of institutional stakeholders and the level of climate change disclosure. The S2 Climate-related Disclosures Exposure Draft (the Draft), published by the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) in March 2022, is structured around four areas, namely, governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics and targets. Details of each area will be discussed below. By issuing a global baseline for climate change disclosure, businesses can become better familiarised with climate change reporting requirements, thus fulfilling the ethical responsibility to the environment.

Current climate change disclosure regimes in the global context

Hong Kong

To strive for carbon neutrality by 2050, Hong Kong’s climate change disclosure standards will be tightened. Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Ltd has proposed to mandate all listed companies to provide climate change disclosure in their ESG reports. This is currently scheduled to take effect from 1 January 2025 and will be introduced as a new Part D of Appendix 27 to the Hong Kong Listing Rules. This will mark an upgrade from the current ‘comply-or-explain’ regime, where issuers are allowed either to make climate change disclosures or to justify their absence.

As the proposal strives to align Hong Kong’s ESG regime with the global climate change disclosure standards, it builds on the Draft (see Figure 2). First, companies must reveal their climate-related goals and whether their attempts to mitigate or adapt to climate change will alter their business models and strategies. Second, they must disclose how resilient their business models are to the effects of climate change, including a quantitative analysis of current impacts and a qualitative description of future impacts on their financial performance, position and cash flows. Third, the percentage of their assets or business operations susceptible to climate risks or aligned with climate-related opportunities, as well as the funding allocated to them, must be disclosed. Fourth, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions for Scope 1, Scope 2 and Scope 3, as well as information on any internal carbon pricing maintained by companies and how climate-related considerations are factored into executive compensation policies, must be revealed.

Prior to the implementation of the mandatory policy, some listed companies, like the Bank of China, CLP Power and Standard Chartered, had already provided climate change disclosures on their own initiative.

The Mainland

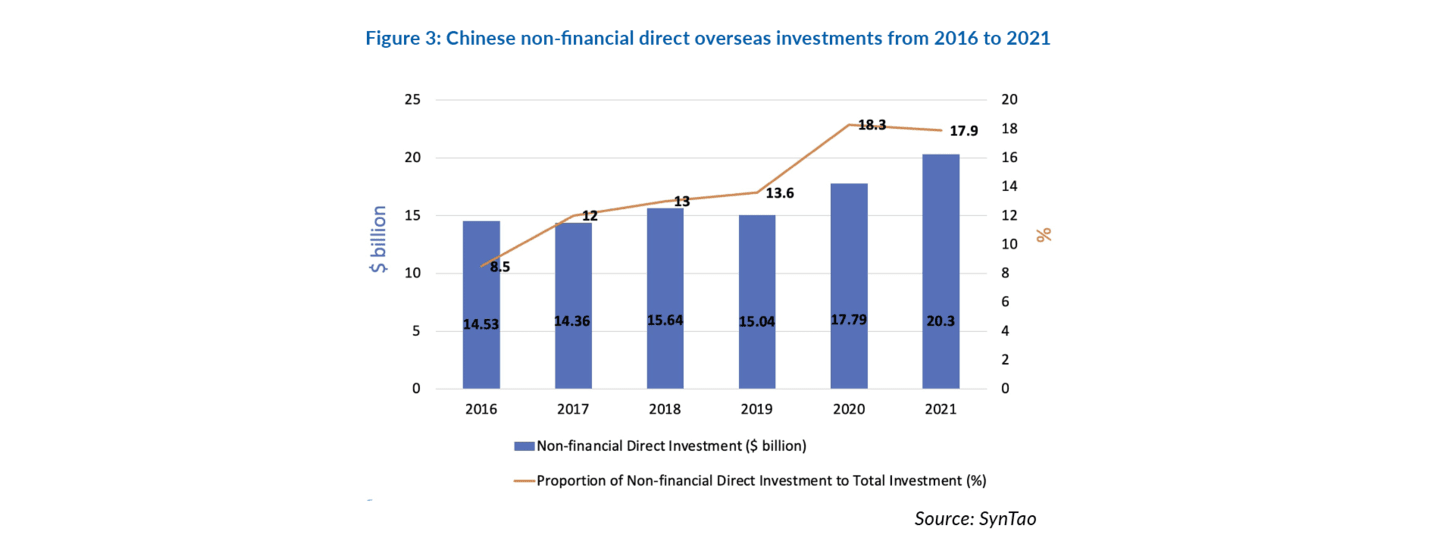

By 2060, the amount required in infrastructure investment, as per the People’s Bank of China, could total between RMB100 trillion and RMB200 trillion. As such, the Mainland employs a top-down strategy to support these goals and was the first nation in the world to create a complete policy framework for green finance, which was launched in 2016. In contributing to the world economy, the overall trend of non-financial direct investment by Chinese enterprises in 57 countries increased from 2016 to 2021, with the proportion of investment also rising year by year (see Figure 3).

Additionally, the Guidance for Enterprise ESG Disclosure (the Guidance) was released by the China Enterprise Reform and Development Society (CERDS), together with several notable Chinese corporations, with effect from 1 June 2022. The Guidance, which applies to all businesses and sectors, is the Mainland’s first ESG disclosure policy. The Guidance outlines a framework for Chinese businesses to report under three core metrics for environmental, social and governance measures, which are further broken down into 10 secondary metrics, 35 tertiary metrics and 118 total metrics. The Guidance’s most significant aspect is how it adjusts ESG principles to the needs of domestic laws and regulations, along with the Chinese business landscape. This is described as ‘international guidelines with Chinese characteristics’. It includes references to the unique features of the Mainland’s social welfare system, such as social security and the housing provident fund.

While compliance with the Guidance remains voluntary, Chinese businesses may leverage it as a springboard to explore the use of ESG standards that have been tailored for and created in a local context. On a broader level, it is anticipated that mandatory ESG disclosures, commencing with state-owned businesses, are likely to be introduced in the Mainland.

Europe

The European Council authorised the adoption of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) on 28 November 2022, which became operative on 5 January 2023. The CSRD mandates reporting and disclosure of data on large enterprises’ societal and environmental impacts, as well as external sustainability concerns affecting their operations. Furthermore, the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (2014/95/EU) has been amended by the CSRD, which additionally establishes more specific, mandatory sustainability reporting standards. These standards involve qualitative and quantitative data on ESG issues, including climate change. Therefore, both large corporations and listed small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) must submit reports on sustainability and governance issues.

The EU has initiated significant progress towards a sustainable economy via upgraded corporate accountability with the shift from ‘non-financial disclosures’ to ‘sustainability disclosures’, which reconciles financial and sustainability reporting. According to estimates, the new regulations will apply to 50,000 enterprises. Companies will need to evaluate their disclosing strategies in light of the CSRD and create systems for gathering pertinent, verifiable data, as well as disclosing relevant details in an unambiguous, efficient manner supported by independent verification.

Critiques of the emphasis on climate change disclosure

In the past decade, the subject of climate change has been receiving greater prominence, with plenty of organisations and governments stressing the urgency of climate change disclosure. Yet, some doubts have been raised about whether the world has become overly focused on climate change disclosure.

Neglecting other ESG goals

To accomplish business sustainability by placing a disproportionate spotlight on climate change disclosure as a countermeasure to environmental threats, companies might overlook other important ESG issues such as labour practices, supply chain management, and diversity and inclusion.

By way of example, Nestlé places an overabundance of weight on how climate-related hazards might impact its strategy and future business forecasts, with its climate change disclosure set up in line with the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) guidelines. As such, the comprehensive disclosure covers its governance structures, strategy and risk management, assessment of resilience, and metrics and targets. Likewise, Nestlé adopted the Net Zero Roadmap, wherein the goal is to achieve zero in-scope emissions by 2050. Furthermore, Nestlé undertook a key step towards integrating climate-based thinking throughout its business in 2022 by including climate assessments in its Strategic Business Units’ and Globally Managed Businesses’ yearly strategic portfolio evaluations. Despite endeavouring to minimise its carbon footprint to meet climate change disclosure requirements,it has been investing considerably fewer hours and resources on other equally vital ESG issues, like health risks and human rights abuses. The International Labour Rights Fund and the courts have filed cases against Nestlé spanning from 2005 to 2021, asserting that children were trafficked, forced into slavery and subjected to regular beatings on a cocoa plantation. In the 2008 Chinese milk scandal, Nestlé products were contaminated with melamine, a chemical that is illegally added to food items to boost their apparent protein content, resulting in the death of six infants and the hospitalisation of 860 others with kidney damage. Therefore, corporations’ overzealous focus on climate change disclosures and disregard for the complete spectrum of ESG risks could result in a distorted emphasis on these topics, undermining their long-term sustainability and performance.

Exploiting the benefits of climate change disclosures

Emphasising climate change disclosure encourages enterprises to differentiate themselves from rivals due to their commitment to ethical principles, while simultaneously providing shareholders with genuine benefits in the form of cost savings through energy conservation measures. Further, the growing consensus is that businesses should take the initiative to integrate sustainable practices into their everyday operations, otherwise they face the risk of ruining their reputation and incurring legal ramifications based on regulations particular to their industry. Due to the potential for value generation and reputational enhancement through green initiatives, such as the issuance of green bonds or investing in renewable energy, businesses are now beginning to devote significant resources to these efforts. Hence, there may be a surplus ‘green economy’ developed in satisfying the requirements for climate change disclosure. For instance, an entity may aggressively engage in renewable energy to raise its environmental profile and meet climate change disclosure standards, but due to resource constraints, it must disregard ESG issues like data privacy. This could give rise to a loss of trust and reputational harm, which will eventually impact long-term sustainability and performance. In this regard, some contend that the world is indeed excessively preoccupied with climate change disclosures.

Challenges faced if the world is too focused on climate change disclosure

Assuming the proposition that the world is too focused on climate change disclosure is justified, such excessive focus may present the following challenges.

Hurdles for SMEs

One of the obstacles is that the efficacy of climate change disclosure as a whole may be hindered by SMEs’ restricted access to resources. Due to their lack of resources and knowledge, SMEs may have difficulties in adhering to the standards for climate change disclosure. In particular, 350 SMEs from 40 countries and more than 20 different industries took part in the 2023 study by the SME Climate Hub. Insufficient funding, according to 55% of respondents, is a significant impediment to putting climate-related policies into action. Nearly half of those surveyed indicated that they would require up to US$100,000 to reach net zero. Extra hurdles, as cited by 58% of respondents, included a lack of skills, resources and knowledge. As a result, they may not be able to provide accurate and complete disclosures, which can impact the overall effectiveness of climate change disclosure frameworks across the board.

Diversion of resources

Another challenge that can arise from a single-minded concentration on climate change disclosure is the potential weakening of coordination and corporate sustainability. Companies may divert resources from other important corporate governance matters, such as supply chain management and labour practices, in order to focus on climate change disclosure. This can result in a lack of coordination and integration of ESG issues, which could eventually render it tougher for businesses to be sustainable. The example of Nestlé presented above illustrates a lack of coordination and integration of corporate governance issues, which may ultimately jeopardise the sustainability of the business in its entirety.

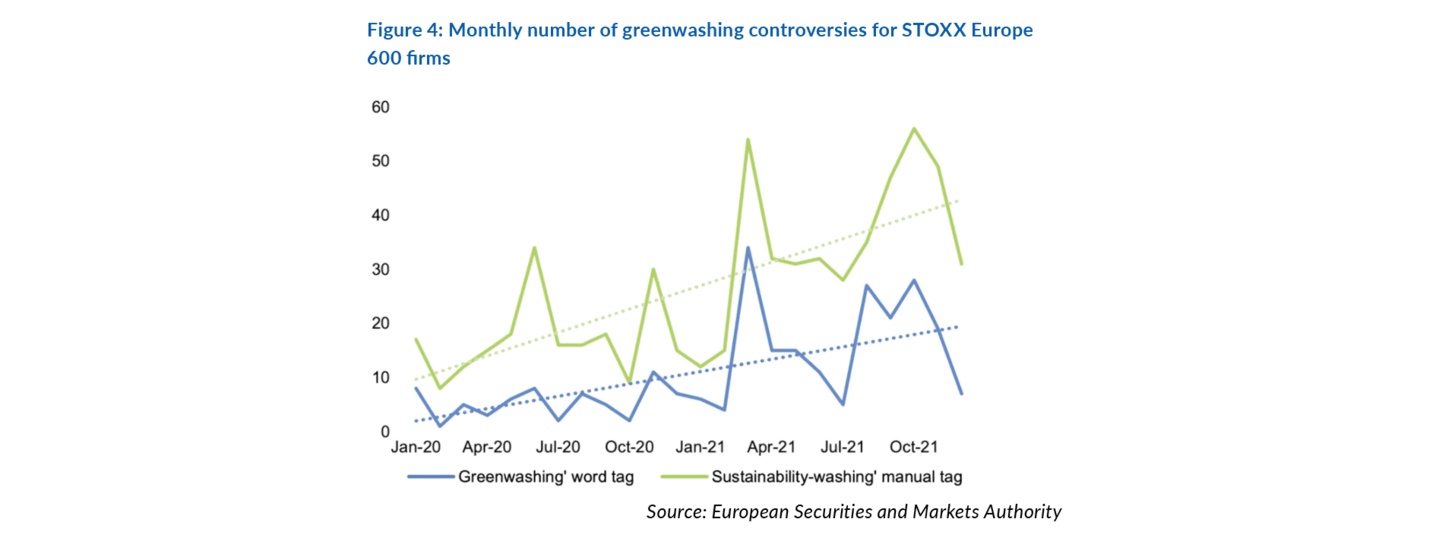

Upsurge of greenwashing

In terms of corporate marketing, climate change disclosure may be treated as a means to raise capital, such as through the issuance of green bonds. While this can be an important step in mitigating climate change, it could result in the practice of ‘greenwashing’, in which businesses’ climate change disclosures lack content or insightful analysis. In Europe, the number of greenwashing controversies has steadily increased between 2020 and 2021 (see Figure 4). The Volkswagen Clean Diesel campaign is one specific instance of greenwashing. Volkswagen promoted its diesel vehicles as being ecologically benign at the beginning of the 2000s, asserting that they had cutting-edge pollution control systems that reduced hazardous emissions. The US Environmental Protection Agency, however, discovered in 2015 that Volkswagen installed software on its diesel vehicles that allowed them to pass emissions tests and conform to disclosure rules regarding climate change. In actuality, Volkswagen vehicles emitted up to 40 times the legal limit of the hazardous pollutant nitrogen oxide. Volkswagen incurred huge reputational damage as a result of the incident and the automaker ultimately had to pay AU$125 million (US$83.4 million) in fines and customer compensation. The Clean Diesel campaign was revealed to be a case of greenwashing as Volkswagen had deliberately misled its customers about the environmental impact of its diesel cars to make it look ‘environmentally friendly’, while providing incomplete or inaccurate climate change disclosures on its risk. The prevalence of greenwashing caused by excessive focus on climate change disclosures thereby creates an unhealthy corporate climate on a global scale.

some contend that the world is indeed excessively preoccupied with climate change disclosures

Yannie Kum and Selina Wu

The University of Hong Kong

This two-part article is the winning paper of the Institute’s annual Corporate Governance Paper Competition for 2023, titled ‘Climate change disclosures: an overlooked priority in the world’s agenda?’, under the theme ‘Climate change disclosures – is the world too focused on this topic?’ More information on the competition and the full version of the Best Paper, along with those from the First Runner-up and Second Runner-up, are available under the Studentship section of the Institute’s website: www.hkcgi.org.hk.