Corporate purpose and stakeholder interests – Corporate Governance Paper Competition 2021 – Best Paper

This second and final part of the Best Paper of the latest Corporate Governance Paper Competition, held by the Institute, identifies the challenges involved in taking the stakeholder approach, and provides solutions for corporations to identify, implement and disclose their purpose.

The Institute holds its annual Corporate Governance Paper Competition and Presentation Awards to promote awareness of corporate governance among local undergraduates. This article is a summary of the Best Paper of the 2021 Corporate Governance Paper Competition. The first part of this paper, published in last month’s CGj, focused on the incentives to exercising purposeful governance from three perspectives – profitability, sustainability and ethics.

The challenges involved in taking the stakeholder approach

Conflicting stakeholder interests

The term ‘stakeholder’ comprises, but is not limited to, financial stakeholders (including shareholders), societal stakeholders, employees, customers and business partners. It is difficult to make conclusions about or rank the importance of stakeholder groups without considering the actual situation of the specific company.

Furthermore, the objectives of corporate governance vary when taking different stakeholder groups into account – profit-maximising for financial stakeholders, contributions of sustainable solutions for societal stakeholders, favourable employment conditions for employees, adding value for customers, cocreating for business partners and so on.

Given the various concerns of different stakeholders, one critical task is to ascertain whether they are compatible or whether they are ‘zero-sum’ – which means that adopting one hinders the other – or to find a solution to turn the zero-sum into a win-win situation. Although some interests can be aligned, conflicts exist in some relationships. For example, there are inherent conflicts of interest in the relationship between principals and agents. In the relationship between shareholders and managers, managers may tend to pursue the short-term interest rather than the long-term interest that is preferable to shareholders. When the bondholder acts as the principal and the shareholder acts as the agent, the problem will be that the stockholder may prefer riskier projects due to the different payoff curves.

With unbalanced stakeholder pursuits, companies would find it difficult to achieve profitability and sustainability. In addition, a company could fall into an ethical dilemma if it ignores some of the minority voices. All these consequences lessen the possibilities for a company to conduct purposeful corporate governance. Only by solving the potential conflicts of multiple interests can a firm successfully manage its stakeholder relationships.

Ambiguous boundaries of stakeholder groups

Following the definition by Freeman, the concept of ‘stakeholder’ gave rise to over 60 explanations. Depending on the particular understanding of the meaning of stakeholder, a company may consider the stakeholder group in a broader or more restrictive range.

It is also challenging for the firm to figure out the exact stakeholder boundaries. Effort is needed to distinguish the constitution of one stakeholder group from another, and to identify which stakeholder group an individual belongs to. It is even more challenging for large conglomerates to determine and manage their stakeholder groups than it is for small enterprises. The difficulty in identifying stakeholders, especially secondary stakeholders, is a phenomenon called stakeholder ambiguity. The ambiguity may indeed undermine the competitive advantage gained by stakeholder managers.

First, without identifying the different stakeholder groups, it would be impossible for the company to balance their concerns. Second, without the classification of various stakeholders, it would be confusing for the company to realise the actual needs of the stakeholders. As a result, the ambiguity hinders the establishment and improvement of purposeful corporate governance with proper stakeholder management.

Theoretical possibilities

Potential alignment of multiple interests

Ultimately, there is no conflict between shareholders’ and stakeholders’ interests. In other words, it is possible to align their interests if a company is aiming for long-term sustainability. As illustrated above, stakeholders are parties who will be affected by any operation or activity of the company, the notion of which is derived from the very existence of a company. Without a long-term goal, and with a focus merely on short-term profit, a company is unlikely to be sustainable and it will therefore be impossible to properly provide for its stakeholders.

The reverse is also the case – a company will not be able to achieve long-term growth without concerning itself with stakeholders’ interests as a whole. Therefore, all stakeholders would be presenting a unified front in terms of the sustainability of the company, at least, and this ‘common expectation or interest’ of all stakeholders appears to suggest the possibility of achieving purposeful governance. Through caring more about environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues, as already discussed, companies can generate extra financial and ethical values, thereby setting up a virtuous cycle that mutually benefits financial and ESG considerations.

Apart from the common interest, there are unique and diverse interests of myriad stakeholders. However, it is noted that one particular purpose can serve more than one party. It is believed that the purpose beyond profit explains why the company exists, and the profit can be a by-product that is highly likely to be naturally created in the process of pursuing the initial purpose. In the same manner, even though various stakeholders exist, it is not necessary that merely a few groups are able to benefit from a decision.

However, it is unnecessary and impossible for a corporation to work for all stakeholders and to fulfil all their expectations. Stakeholder groups may have diverse special interests and it is not easy to cater to all tastes. Moreover, this is similar to the theory of economies of scale, where only within a certain production level can the company keep reducing production costs to finally reach the most profitable point.

Minimum requirements for directors

As corporations are in the public domain, legally speaking, directors must comply with certain requirements when making decisions. As fiduciaries, directors must disclose their interests when necessary, and cannot take the opportunity for themselves when they come across an opportunity initially intended for the company. Besides, they must exercise their power bona fide in the best interests of the company. The ‘interests of the company’ means the financial interests of the members as a general body, flowing from maximisation of the company’s profits. According to Darvall v North Sydney Brick & Tile Co Ltd, directors would be entitled to act in the long-term or short-term interests of the shareholders as a whole. However, we cannot find an exhaustive list of considerations that directors must take into account when making decisions.

Nevertheless, the disputable issue is whether directors can take account of ESG factors, even though that may not directly lead to profits in the short term. Courts have discussed this issue for several decades. As a result, even though there is no explicit requirement for directors to take ESG considerations into account, the current position – and the likely future direction – suggests that directors can take account of ESG factors, as long as it benefits the company at any stage or that the long-term benefit surpasses the short-term loss. Therefore, decisions such as attractive remuneration for employees and promotional offers for customers can be consistent with directors’ duties.

Practical possibilities

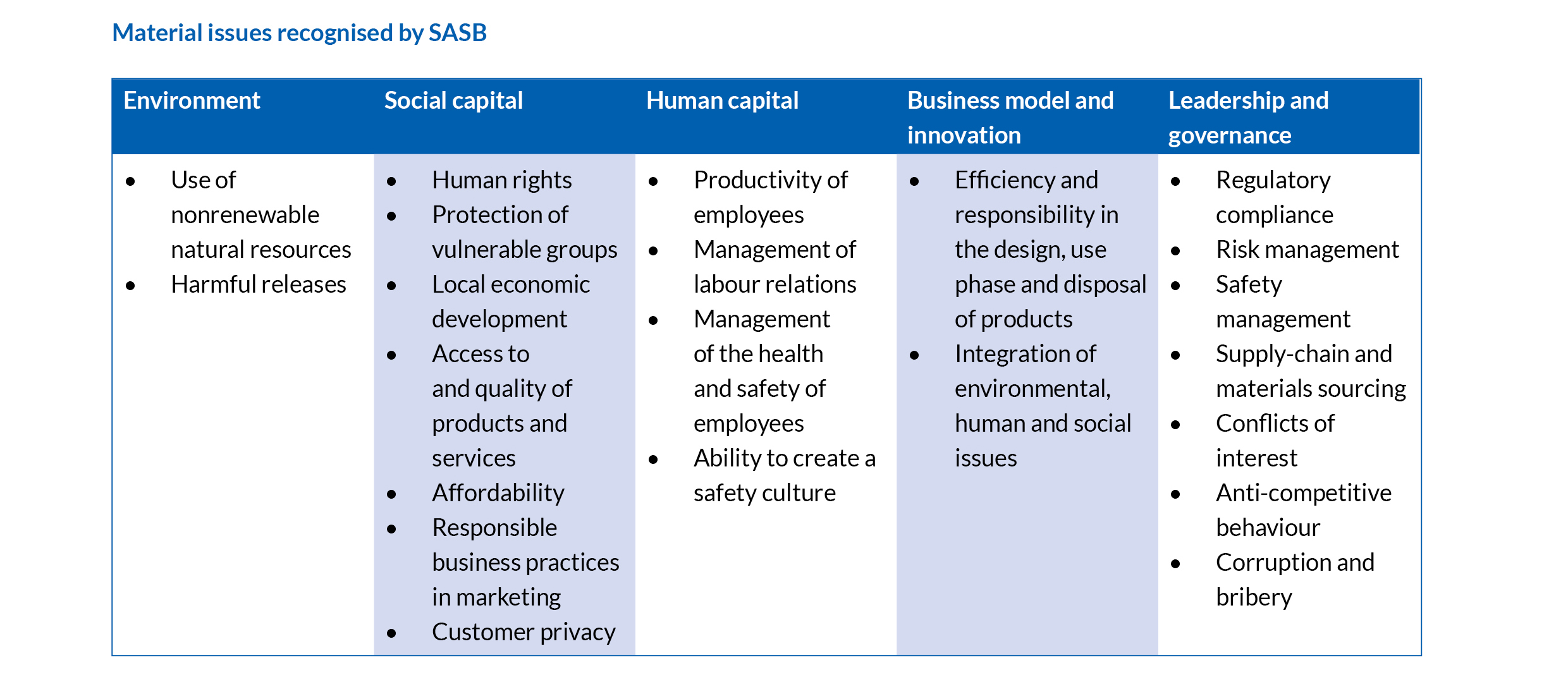

In practice, companies can understand and identify their purpose by prioritising multiple interests and emphasising material ones. Several organisations, such as the International Integrated Reporting Council, the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), have published sustainability standards to assist companies in identifying, deciding on and prioritising material issues that ultimately indicate the companies’ purpose. For example, SASB summarises and classifies material issues into five sections: environment, social capital, human capital, business model and innovation, and leadership and governance (see ‘Material issues recognised by SASB’).

The two most notable reporting standards, GRI and SASB, take distinct but complementary approaches to materiality. SASB emphasises the influence of sustainability issues on the company’s financial performance, whereas GRI focuses on the external impact of the company’s operations and business activities on the economy, environment, people and human rights. Hence, the emerging best practice will be a matrix utilising both important dimensions.

Identification of material issues

Each company is unique and therefore must have its unique materiality portfolio. Before the materiality assessment process, companies should research and review industrial benchmarks, their own internal business and global standards to narrow the fields. For instance, product safety is essential in the auto industry, while data security has received much attention in the tech sector. Some stakeholders, such as investors, are crucial to almost all companies.

1. Communication with stakeholders. There is no doubt that stakeholder engagement matters. It is vital to understand and emphasise how stakeholders consider ESG factors in their decision-making, as well as to take account of their views on current and future ESG programmes. One possible way to obtain the relevant information is to establish a stakeholder board that runs over and above the board of directors, one that is determined by the shareholders. The stakeholder board could consist of representatives from shareholders, employees, significant consumers, significant suppliers, lenders, communities and investors, among others. Additionally, companies are advised to introduce some experienced corporate professionals and relevant experts who are competent in reporting, screening and prioritising processes. By doing so, critical internal and external stakeholders will be identified and engaged regularly in a structured manner.

The materiality identification is not a ‘one and done’ exercise, and should be refreshed frequently in order to address emerging issues and business contexts, which, as Covid-19 has shown, can rapidly shift.

2. Customer-related compliance and the ‘right thing to do’. Customers are one of the most critical stakeholders. In terms of a customer-related compliance framework, the main focus for a corporation would be on the distinction between the minimum legal requirements and CSR. One example is the tax affairs of well-known companies such as Starbucks, Google and Facebook in 2013. These companies all managed to avoid being taxed on their UK revenues. While the measures adopted by the companies were legal, they were widely seen as unethical as they were utilising loopholes in the British tax system and robbing public services. The hostile public reaction to Starbucks’ tax dealings, for instance, led them to pledge £10 million in taxes for each of the next two years, in an attempt to win back customers.

3. Internal control and risk management. Increased concerns have recently arisen regarding corporate accountability. A comparative study between Australia and Belgium suggested that a weaker focus on risk management and internal control within corporate governance guidelines may result in a less-developed system. Even though the external environment provides a different level of focus and support, corporations are competing in a relatively free global market. They should thus consider an internal control and risk management framework at an early stage, even without government or regulatory guidelines.

Striking a balance

Among the difficulties mentioned above, the most troublesome is balancing multiple interests, as stakeholder interests can conflict. Measures need to be taken to help with the balancing exercise, and the balanced scorecard (BSC) can be introduced for this purpose.

BSC could be applied to allow directors to analyse their business from four perspectives: finance, internal business, innovation and learning, and customers. This would enable them to emphasise the central issue and to help avoid being distracted by other gradually appearing measurements. It also guards against suboptimisation, as it allows managers to consider all critical factors together, rather than sacrificing one goal for another.

Implementation of material issues

Companies can sometimes struggle to get everyone on the same page, especially when other business units have different priorities and goals that may well align with corporate goals for the bottom line, but not necessarily with their ESG initiatives. To ensure the implementation of identified material issues, a company should integrate material ESG issues into its business strategy, functions and operations. Educational initiatives, training and a unified approach to internal business practices and controls can help secure employee engagement and support from the executive levels.

The stakeholder matrix may assist in executing the ‘purpose’. After identifying materiality, four groups of stakeholders are formed using the significance of stakeholders’ influence and their related interests. Different strategies are applied correspondingly: closely managing the stakeholder group with high interest and big influence, keeping satisfied those with low interest and big influence, keeping informed those with high interest and low influence, and continuously monitoring those with low interest and low influence. Tailored strategies targeting different groups help the company to optimise the implementation with the greatest efficiency.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is possible for firms to institute purposeful corporate governance while taking into account a myriad of stakeholders’ interests. Based on stakeholder theory, purposeful corporate governance requires a company’s efforts in stakeholder management, which in turn benefits the company. Going beyond profit, the corporation is also driven by sustainability and ethics to take the stakeholder approach.

Although difficulties – including inherent conflicts and ambiguity of stakeholder groups – can still hinder stakeholder management, feasibility lies in the potential alignment of interests and the legal environment. In the meantime, firms’ efforts are needed in pre-implementation, implementation and post-implementation. Before the implementation, the understanding and identification of stakeholders should be given emphasis, and BSC can help to strike a balance. During the implementation, separate strategies can be integrated by using the stakeholder matrix. After the implementation, disclosure can be made through ESG reports. With both pursuits and feasibility, there are possibilities for corporate governance tied with a myriad of stakeholders’ interests.

Shevin Fan, Isaac Lee, Hellen Liu and Magnolia Wang

City University of Hong Kong

More information relating to the Institute’s Corporate Governance Paper Competition and Presentation Awards was published in the Student News section of the November 2021 edition of this journal.