Enhancing the governance of charitable institutions in Hong Kong

In the absence of an effective regulatory framework for charities in Hong Kong, Chee Keong (CK) Low FCG HKFCG, Institute Council member and Qualifications Committee Chairman, makes suggestions to ensure that governance best practices are followed in the sector.

Highlights

- the potential for malpractice by charitable institutions (CIs) in Hong Kong is real as the existing regulatory regime is fragmented and ineffective

- as a first step, CIs should be required to appoint a qualified company secretary with the responsibility, together with members of the board, to ensure that good governance practices are followed

- establishing a Code of Best Practice for CIs, which could be subject to the comply or explain enforcement mechanism, would also be a significant step towards promoting a wider culture of good governance in the sector

Almost a decade ago in an opinion piece in Forbes titled ‘Is Hong Kong a paradise for charity fraudsters? It surely could be’, the respondents to a survey were prescient to stress that in order ‘to avoid future undesirable incidents, Hong Kong should improve its regulatory framework for charities and increase the awareness of the need for good governance in this sector’.

This proved to be sound advice, as evident from two recent widely publicised incidents, namely at the Christian Zheng Sheng Association – a charity set up to help adolescents with drug addictions – whose directors were arrested on suspicion of conspiracy to defraud HK$50 million in donations, and abuses of more than 35 toddlers at a care home, which led to the resignation of the Director of the Hong Kong Society for the Protection of Children and the conviction of a number of its erstwhile employees.

While these are hopefully isolated cases, they nonetheless highlight the utmost importance of good governance best practices. In particular, accountability and transparency are especially important in charitable institutions since their funding depends largely on public trust and perception.

accountability and transparency are especially important in charitable institutions since their funding depends largely on public trust and perception

Some statistics

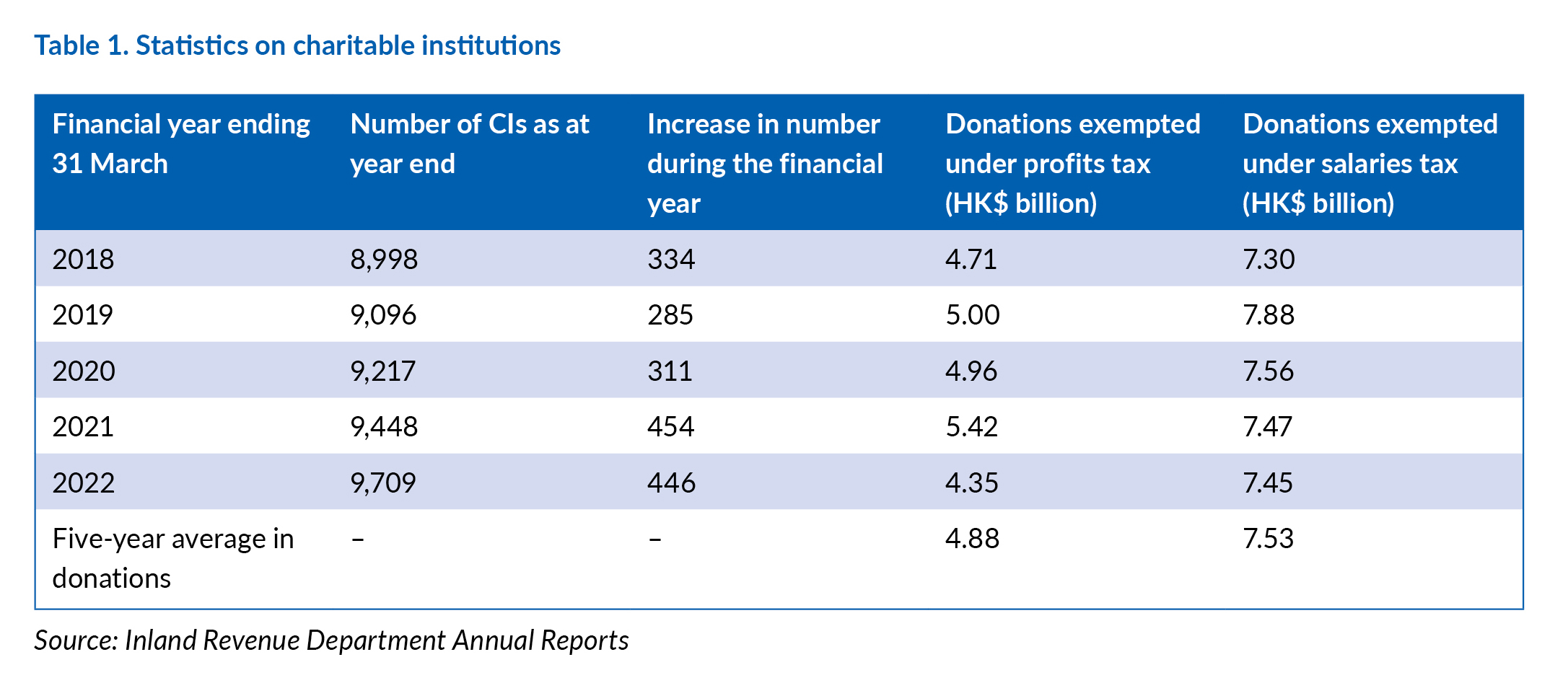

As evident from Table 1, the number of charitable institutions (CIs) that have been accorded tax exemption under section 88 of the Inland Revenue Ordinance has increased steadily over the past five years. Yet, despite the substantial amount of public funds that are raised annually by these CIs, it remains an anomaly that attempts to regulate their activities have not been successful. Indeed, in a research report titled Regulation of Malpractice of Charitable Organizations by the Legislative Council, it was observed that CIs are:

‘… currently subject to weak oversight, as regulatory responsibilities are dispersed among 18 bureaux and departments. Due to regulatory gaps with lack of coordination, reports concerning mismanagement and malpractice of charities occur from time to time, including improper usage of public donations and operation of profit-making hotels on land granted by the government at nil or concessionary premium. Not only have these scandals undermined public trust in the charity sector, they also have led to widespread concerns that the existing regulatory regime is “fragmented and ineffective”.’ (emphasis added)

despite the substantial amount of public funds that are raised annually by these charitable institutions, it remains an anomaly that attempts to regulate their activities have not been successful

In fact, the regulatory framework for charities in Hong Kong has been reviewed by no less than five public bodies – the Audit Commission, the Independent Commission Against Corruption, The Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong, the Office of the Ombudsman and the Public Accounts Committee – over the past 15 years, with most recommending that:

- there be a maintenance of a Register of Charities that meets a statutory definition

- fundraising activities be regulated, and

- there be adequate and appropriate safeguards for the proper usage of public donations.

While a number of common law jurisdictions, including Australia, Singapore and the UK, have implemented regulatory reforms to improve the accountability and transparency of their charities, the HKSAR Government has instead chosen to simply introduce some administrative measures to improve transparency of fundraising activities on the grounds that there is ‘no consensus in the community’ for a more comprehensive framework, despite The Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong suggesting the setting up of a single regulator.

Regulatory gaps

The absence of a single regulator and indeed the absence of a statutory definition of the terms ‘charity’ and ‘charitable purposes’ – under the Inland Revenue Ordinance these terms remain premised upon English case law from 1891, which principally covers poverty relief, education and religious purposes – has been identified as potentially giving rise to a number of shortcomings. These include:

- the inability of the Inland Revenue Department (IRD) to withdraw the charity status and/or to demand corrective measures for the misuse of funds, as the IRD can only revoke the tax-exempt status under limited circumstances, such as the cessation of operations, the non-response to its enquiries or the failure to maintain a charitable nature

- the lack of information as charities do not need to disclose the use of proceeds collected from the public through certain forms of fundraising, such as online and/or direct debit, and the government lacks the requisite regulatory power to request this

- charities that do not receive any government subsidies, and which operate in the form of a society or trust, are only subject to minimal scrutiny as the IRD merely requires such charities to submit annual accounts from time to time, usually once every three years, and

- the absence of a single one-stop information portal makes it difficult, if not impossible, for the public and donors to monitor the governance and financial situation of the almost 10,000 charities that enjoy tax exempt status.

The potential for malpractice with CIs is real – ranging from the improper use of funds to the high administrative costs of fundraising activities that effectively reduce the amount to be applied towards the ‘charitable purpose’ for which it was intended – the most recent examples of which are the Christian Zheng Sheng Association and the child abuse by staff members at the Mongkok residential home operated by the Hong Kong Society for the Protection of Children.

Against this background, real and tangible evidence of the benefits of instituting and implementing reforms can be seen in Australia, where the establishment of the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission in December 2012 was affirmed as being ‘largely effective’ by the Australian National Audit Office in 2020 in achieving its objects. These were to:

- maintain, protect and enhance public trust and confidence in the Australian not-for-profit sector

- support and sustain a robust, vibrant, independent and innovative not-for-profit sector, and

- promote the reduction of unnecessary regulatory obligations on the sector.

A proposal for better governance of CIs

Taking cognisance of the fact that any proposal for the establishment of a statutory framework for CIs would take considerable time, given the legislative processes involved, a noteworthy first step might be mandating the appointment of a qualified person to assume the office of company secretary, or its equivalent, with the ultimate objective being to come up with a Code of Best Practice for charitable institutions.

To this end, some preliminary guidance may be obtained from the Main Board Listing Rules 3.28 and 3.29, which set out the existing requirements for listed issuers to appoint a qualified and appropriately experienced company secretary (see: Main Board Listing Rules 3.28 and 3.29).

Main Board Listing Rules 3.28 and 3.29

Listing Rule 3.28. The issuer must appoint as its company secretary an individual who, by virtue of his or her academic or professional qualifications or relevant experience, is, in the opinion of the Exchange, capable of discharging the functions of company secretary.

Notes:

1. The Exchange considers the following academic or professional qualifications to be acceptable:

- a member of The Hong Kong Chartered Governance Institute

- a solicitor or barrister (as defined in the Legal Practitioners Ordinance), and

- a certified public accountant (as defined in the Professional Accountants Ordinance).

2. In assessing ‘relevant experience’, the Exchange will consider the individual’s:

- length of employment with the issuer and other issuers, and the roles he or she has played

- familiarity with the Listing Rules, and other relevant laws and regulations, including the Securities and Futures Ordinance, Companies Ordinance, Companies (Winding Up and Miscellaneous Provisions) Ordinance and the Takeovers Code

- relevant training taken and/or to be taken in addition to the minimum requirement under rule 3.29, and

- professional qualifications in other jurisdictions.

Listing Rule 3.29. In each financial year, an issuer’s company secretary must take no less than 15 hours of relevant professional training.

The existing Listing Rule requirements for company secretaries of listed issuers could be adapted in such a manner as to be appropriate for the purposes of strengthening the quality of human resources in the administration of CIs. This would be of significant importance to protecting and enhancing public confidence, given that some HK$12 billion was donated on an annual basis over the five-year period ending 31 March 2022.

The integrity, as well as the ‘fitness for purpose’, of human resources – premised inter alia upon the appointment of a qualified person to be the company secretary of the CI as its ‘responsible person’, together with members of its board – supports and sustains the confidence of donors, which ultimately enhances the benefits received by the intended beneficiaries in an accountable and transparent manner.

With the quality of human resources enhanced, the next step would be the conduct of broad consultation amongst various stakeholders, including corporate donors, the public, non-government organisations (NGOs), CIs and the government, to come up with a voluntary but widely accepted Code of Best Practice for charitable institutions (the Code).

Significantly, while compliance with the Code would not have to be mandatory, it would be prudent in the journey towards promoting a wider culture of good governance practices by CIs to put in place a comply or explain regime, whereby the board of the CI would have to explain why they have not complied with any of the provisions and/or why certain provisions do not apply to them. Such disclosure enhances accountability and transparency, which would increase confidence amongst donors that their donations are going to objectives that they support.

Again, in this respect, there is no need to reinvent the wheel as invaluable guidance on the proposed Code can be obtained locally from such platforms as the NGO Governance platform that was initiated by The Hong Kong Council of Social Service, or internationally from the Charity Governance Code – a UK-based practical guide that assists charities and their trustees to develop high standards of governance. These could provide relevant benchmarks in an ‘adaptable’ manner that best suits the requirements of CIs and meets with public expectations in Hong Kong.

Looking further ahead

There is no reason why we should stop with the appointment of a qualified person to be the company secretary of a CI – or an NGO – as thought should be given towards an amendment to the Companies Ordinance to require all companies that are incorporated in Hong Kong to have the same framework.

This will ultimately contribute towards the standards of professionals, their professionalism and the quality of their services – given the need for the attainment of certain internationally recognised qualifications, as well as the need for continuing professional development. These measures would contribute towards the enhancement of good corporate governance practices in line with the aspirations of the government towards this objective.

Further reading

Further information on the issues raised in this article can be found in the websites listed below.

- https://www.hkreform.gov.hk/en/index/index.htm – The Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong’s Report on Charities

- https://www.acnc.gov.au/ – Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission

- https://governance.hkcss.org.hk – NGO Governance platform set up by The Hong Kong Council of Social Service

- https://www.charitygovernancecode.org/en – Charity Governance Code (a UK-based initiative to help charities and their trustees develop high standards of governance)

Chee Keong (CK) Low FCG HKFCG

In addition to being a member of the Institute’s Council, the author is Chairman of the Institute’s Qualifications Committee and Chairman of the Institute’s Investigation Group. He was formerly Associate Professor in Corporate Law at The Chinese University of Hong Kong Business School. His research has been published in journals in Australasia, Europe and the US. He has served on numerous Institute committees and working groups. In addition, he is currently a member of the statutory Advisory Committee of the Accounting and Financial Reporting Council and the Standing Committee on Company Law Reform in Hong Kong. He has previously served on the Listing Committee of The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Ltd and on the Securities and Futures Appeals Tribunal.