Hong Kong’s new ESG Code – are you ready? - ACRU 2024 review – part one

The Institute’s 25th Annual Corporate and Regulatory Update (ACRU), held in hybrid mode on 7 June 2024, was a useful opportunity to get all the latest information and advice regarding the incoming regime for climate disclosures in Hong Kong. CGj highlights the key takeaways relevant to this, as well as other top compliance and governance concerns discussed at the forum.

Highlights

- all Main Board listed companies will be required to disclose Scope 3 GHG emissions on a comply-or-explain basis from January 2025 and, for LargeCap issuers, this requirement will become mandatory from January 2026

- to address issuers’ concerns about the more challenging climate-related disclosures, four different categories of implementation relief have been introduced

- even where directors and professional practitioners are not directly involved in fraud, they may find themselves subject to enforcement actions by regulators for their part in the control failures that permitted the fraud to take place

This year, the Institute’s ACRU forum is celebrating its 25th birthday. Clocking up a track record of a quarter of a century is no small feat for a CPD forum and many speakers at this year’s event commended the Institute on this achievement.

ACRU has grown to become the most popular ECPD event hosted by the Institute. The one-day conference brings together governance stakeholders in an open dialogue about the top issues in governance and compliance. This year’s forum updated participants on everything from regulatory filing dates to high-level reminders about what good governance and compliance should look like.

Preparing for Hong Kong’s enhanced climate-related disclosure regime

In his ACRU presentation, Paul Malam, Head of Policy and Secretariat Services, Listing Division, Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited (HKEX), gave practical guidance on how companies can prepare for the new climate-related disclosure requirements soon to be implemented under Part D of the ESG Code in the Listing Rules.

GHG emissions disclosures

The new requirements applicable to the disclosure of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, in particular Scope 3 GHG emissions disclosures, have been getting a great deal of attention from the market. Since Scope 3 emissions comprise those generated by the entities in issuers’ value chains (including both upstream suppliers and downstream customers), collecting the relevant data is likely to be a challenge.

Recognising this, together with the fact that listed companies in Hong Kong vary greatly in terms of the resources and capabilities available to them, HKEX has opted to phase in the requirements relating to Scope 3 GHG emissions in a way that allows smaller-scale issuers more time to prepare.

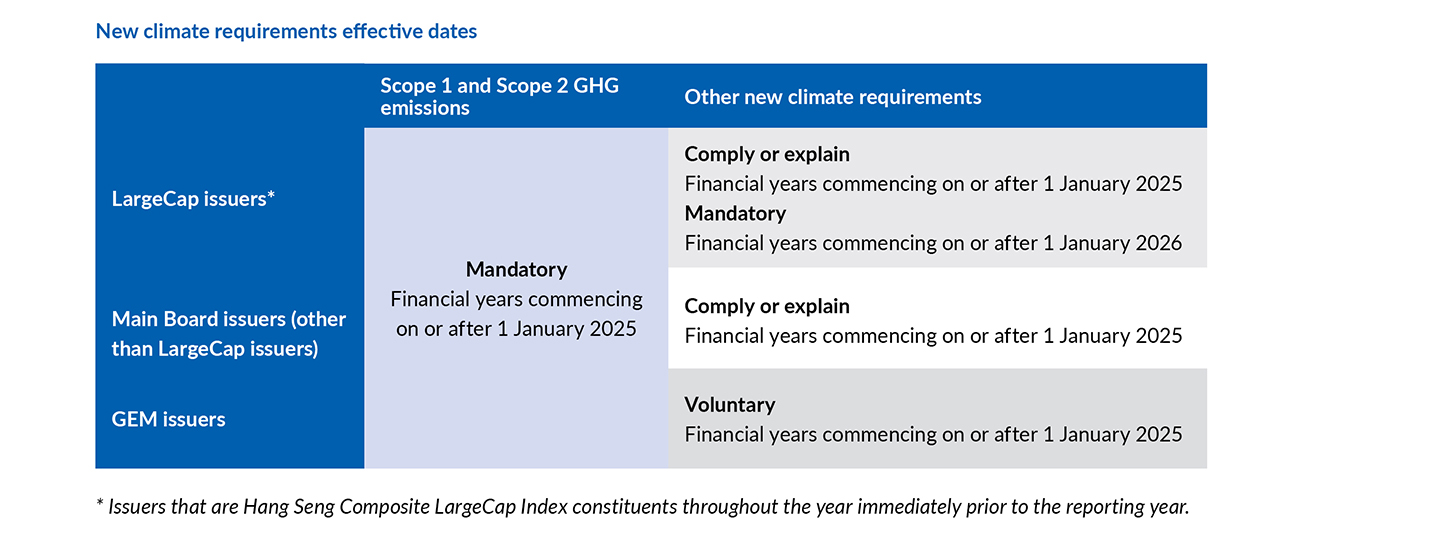

It will be mandatory for all listed companies to report on their Scope 1 and Scope 2 GHG emissions (those generated by the issuer itself and from its energy purchases, respectively) from financial years beginning 1 January 2025. This is quite straightforward and Mr Malam pointed out that over 93% of issuers are already in compliance.

Scope 3 disclosures will be subject to ‘comply or explain’ for all Main Board issuers from financial years commencing on or after 1 January 2025. For LargeCap issuers (constituents of the Hang Seng Composite LargeCap Index), Scope 3 reporting will become mandatory from financial years commencing on or after 1 January 2026 (see ‘New climate requirements effective dates’). GEM issuers will be given the flexibility to report on Scope 3 and the other new ESG Code requirements on a voluntary basis.

Implementation reliefs

Mr Malam added that Scope 3 disclosures will also be subject to a ‘reasonable information relief’ – meaning that organisations will only be required to report reasonable and supportable information available at the reporting date that can be obtained without undue cost or effort. Four implementation reliefs have been introduced to address concerns over the reporting challenges that issuers may face. In addition to the reasonable information relief, some of the new ESG Code requirements will be subject to a:

- capabilities relief – organisations will only be expected to report to a level based on the skills, capabilities and resources available to them

- commercial sensitivity relief – organisations will not be required to disclose climate-related opportunities if that would seriously prejudice the economic benefits that could be realised in pursuing such opportunities, and

- financial effects relief – where the financial effects of climate change are difficult to quantify, they may be disclosed on an aggregated basis, or organisations may opt to give qualitative disclosures.

HKEX recognises that sustainability reporting is a journey and it would be unrealistic to expect perfection from day one, Mr Malam said. Accordingly, it has published its Implementation Guidance for Climate Disclosures, which provides practical guidance on preparing relevant disclosures. The Implementation Guidance, for example, includes a table of sources of publicly available scenario models to assist issuers in their compliance with the requirement to disclose the impact of different scenarios of climate change on their business. Moreover, Mr Malam added that issuers should adopt a method that is commensurate with their circumstances in its scenario analysis.

‘In its first ESG report, an issuer can use qualitative storylines and then try to beef up the disclosure in subsequent reports. We don’t expect perfection from the very start,’ he said.

The bigger picture

To conclude, Mr Malam pointed out that the new ESG Code requirements are part of a larger roadmap for Hong Kong. They represent the first step in preparing listed issuers for the sustainability disclosure standards currently under development by the Hong Kong Institute of Certified Public Accountants (HKICPA).

HKICPA is the standard-setter for developing local sustainability disclosure standards aligned with those of the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB). The Hong Kong standards are intended for cross-sectoral observance, including for listed companies and regulated financial institutions. The government will work with financial regulators and stakeholders to launch a roadmap on the appropriate adoption of the ISSB Standards within 2024 to facilitate green and sustainable financial services.

Managing conflicts of interest

Conflicts of interest have been a growing area of enforcement work for HKEX and Jon Witts, Head of Enforcement, Listing Division, HKEX, anticipates that it will continue to be a major theme of its investigations.

His main message was that conflicts can arise in many different forms, including between the interests of an organisation and the personal interests of individuals working for it, and also when an individual has potentially conflicting duties to different organisations. The law and regulations do not give a full checklist of what constitutes a conflict, but they do make clear that the scope is broad and that directors are under a very wide duty to be transparent about any potential conflict. It is not a defence for directors to argue that, since they were not influenced by the potential conflict, they didn’t need to declare it.

‘If you even think there’s a sniff of a conflict, then you need to do something about it – speak up, get it addressed, get it out in the open,’ he said.

Mr Witts added that declaring a conflict doesn’t necessarily mean that the relevant business has to be abandoned. In fact, it is the transparency that enables the conflict to be managed properly and therefore potentially for the business to proceed.

Where theory meets practice

Conflicts of interest are also a central concern of the Hong Kong Business Ethics Development Centre (HKBEDC) of the Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC). This year’s ACRU was fortunate to have Mary Lau, Executive Director of the ICAC’s HKBEDC, to speak on this theme. Her presentation focused on best practices with real-life scenarios.

When to avoid and when to declare. What should you do if you are approached by a friend who asks you to help him or her apply for a new position at your company? The relevant principle to bear in mind here is the need to ‘avoid or declare’ a conflict of interest. Whether to avoid or declare, Ms Lau pointed out, would be based on your own involvement in the hiring process. If you are not involved, you can avoid the conflict of interest by telling your friend to contact the relevant department handling the hiring process. If you are involved, you would need to declare to the company as soon as possible your potential conflict to protect yourself and achieve the transparency mentioned by Mr Witts earlier. Arrangements should then be made by the company to manage the declared conflict of interest.

Mishandling conflicts of interest can distort and cast doubt on the reliability of one’s professional judgement, attracting criticism and suspicion. In addition to breaching the code of conduct of the company or the profession, it can lead to criminal offences such as deception or conspiracy to commit fraud, if fraudulent acts such as falsifying documents to conceal conflicts are involved. On the other hand, if an advantage is offered or accepted during the mishandling of conflicts of interest, it may constitute a breach of the Prevention of Bribery Ordinance (POBO).

When is a gift a bribe? The POBO, which is enforced by the ICAC, establishes the offence of offering and receiving a bribe with potential penalties including imprisonment for seven years and a fine of HK$500,000.

Nevertheless, there can be circumstances when the right way to handle this common conflict of interest scenario is not immediately obvious. The Q&A at the end of Ms Lau’s presentation raised a question relevant to this issue. If an employee of a service provider is offered a gift from a client in appreciation of his or her work, could this be deemed as bribery?

In answering this question, Ms Lau referred to the four defining elements of a bribery offence under the POBO, which can be easily memorised as the ‘four As’ – any Agent may commit a bribery offence if, without his or her principal’s Approval, he or she solicits or accepts any Advantage for any Act in relation to the principal’s affairs. The offeror of the advantage in such circumstances may also contravene the POBO.

Ms Lau pointed out that in the scenario described above, the employee is an agent while the gift, regardless of its monetary value, is an advantage offered in relation to the agent’s official duty. The employee should therefore refer to the company’s code of conduct to see whether staff are allowed to accept advantages on stated conditions and should seek approval from the principal for the acceptance if necessary. Ideally, the code should specify the conditions under which the company allows staff to receive advantages – for example, where the interest of the company will not be impaired and the staff member’s objectivity will not be affected, the advantage is not solicited and the value of the advantage is nominal.

Accountability for control failures

The importance of having effective internal controls is a staple ACRU theme. Regulatory investigations that uncover fraud or malpractice invariably also uncover underlying problems with the internal controls that are supposed to prevent fraud and malpractice from occurring.

This year, however, there was an added dimension to this theme – who should be accountable for failures of internal controls? In this context, Mr Witts pointed out that regulators and law enforcement agencies globally are increasingly taking the view that those directly guilty of malpractice are not the only legitimate target of investigation and enforcement.

‘No matter what capacity you’re in, whether you’re a director or working with the directors, whether you’re an internal or external auditor – everyone’s got a role to try to make sure that bad things can’t happen,’ he said.

He pointed out that the controls in place to ensure compliance and good governance are predicated on the responsibility of key individuals to play their part in monitoring what is going on and stepping in where problems arise. Even where such individuals are not directly involved in malpractice, they may find themselves under investigation for their part in the control failures that enabled the malpractice.

Similarly, the presentation by Flora Ma, Director, Corporate Finance Division, Securities and Futures Commission (SFC), highlighted both the deliberate schemes by individual directors and senior managers to defraud the company and the shareholders, and the board’s failure in its duty to make proper inquiries and exercise independent judgement.

She emphasised that directors have a responsibility to develop and maintain appropriate and effective internal controls and risk assessment systems to safeguard the company’s assets, prevent and detect fraud, and ensure the accuracy of the company’s financial reports. Directors should also regularly review and assess the effectiveness of the internal control systems and make appropriate enhancements where needed.

‘We believe a robust internal control system is the cornerstone of good corporate governance, enabling directors to fulfil the expectations of shareholders and stakeholders, and to guide the companies to sustainable growth and success,’ Ms Ma said.

Her colleague and fellow ACRU presenter, Charles Chan, Director, Enforcement Division, SFC, also addressed this theme. He discussed the recent case against Mayer Holdings Ltd before the Market Misconduct Tribunal (MMT) in which nine current and former senior executives were fined a total of HK$4.65 million for late disclosure of inside information. In addition, the MMT imposed disqualification orders against the executives, one of whom was a former company secretary and financial controller of the company.

‘Senior executives of listed companies, including executive and non-executive directors and company secretaries, have duties to implement effective corporate governance, to ensure full compliance with the law and the rules and regulations, and to prevent and detect occurrences of corporate fraud and misconduct. They should be inquisitive, professional and diligent, and should act with integrity. Our job is to hold those who fail to discharge their duties personally accountable. Each one of us needs to do our part to uphold financial market integrity in Hong Kong as an international financial centre,’ Mr Chan said.

The fact that a key defendant in the Mayer Holdings case was a company secretary brought the message home to the ACRU audience that the responsibilities of governance professionals come with elevated liabilities. Ms Lau of the HKBEDC urged governance professionals to recognise and uphold their professional calling.

‘Just as a doctor’s calling is to heal patients and a lawyer’s calling is to uphold the rule of law, the calling of a governance professional is to serve as the guardian of good governance, thereby contributing to Hong Kong’s economic stability, prosperity and level playing field,’ she said.

“Just as a doctor’s calling is to heal patients and a lawyer’s calling is to uphold the rule of law, the calling of a governance professional is to serve as the guardian of good governance”

Mary Lau

Executive Director, Hong Kong Business Ethics Development Centre, Independent Commission Against Corruption

She added that governance professionals are in a unique position to assist organisations to uphold the highest standards of governance and to build up a strong ethical culture. They should use their expertise in risk management, compliance and stakeholder engagement to promote and shape organisations’ compliance and integrity cultures.

Don’t miss the Climate-related Disclosure Update hybrid seminar to be hosted by the Institute and HKEX on 31 July 2024. More details are available on the Institute’s website: www.hkcgi.org.hk.