Nana Li, Research and Project Director, China, the Asian Corporate Governance Association (ACGA), answers some important questions about variable interest entities (VIEs) and discusses the future implications for Mainland companies using this structure.

A listing loophole used by tech firms such as Alibaba and Tencent to list overseas recently received a PRC regulatory stamp of approval. What is a VIE, why is it controversial and what does the future hold for these structures?

What is a VIE?

A VIE is a corporate structure used by privately owned Mainland companies, including Alibaba and Tencent, to circumvent PRC restrictions on direct foreign investment in key sectors such as telecoms and the internet. It was first used by Sina Corp for its 2000 listing on Nasdaq in the United States and hundreds of other firms have followed suit over the past 20 years, enabling them to raise billions of dollars from foreign investors.

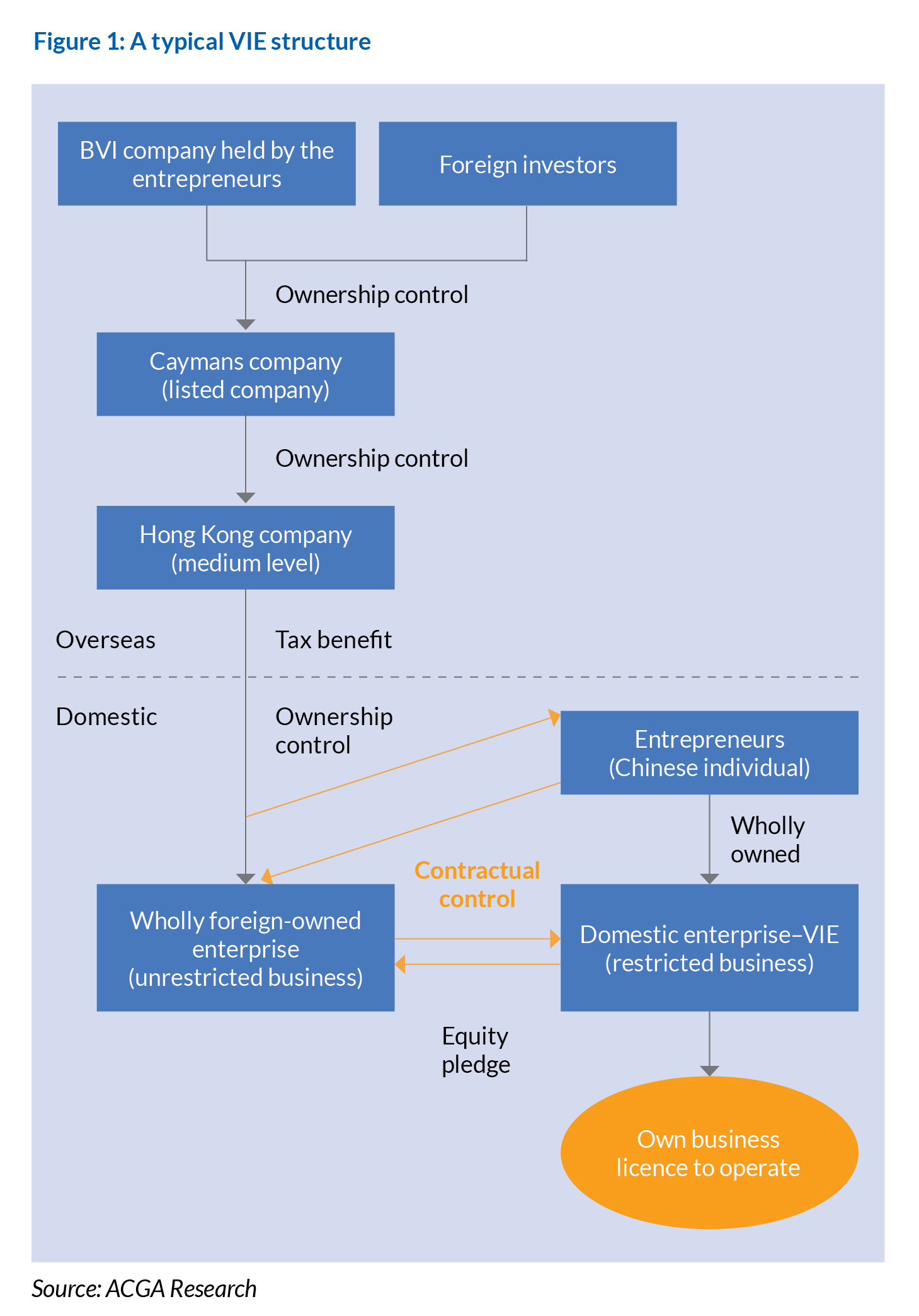

In a VIE structure, foreign shareholders own shares in a shell company – often registered in the Cayman Islands (Caymans) or the British Virgin Islands (BVI) – and use complex contracts to control the operating entity inside the Mainland (see Figure 1).

Why are VIEs controversial?

For years, VIEs have stood on shaky legal ground. If strictly interpreted according to Mainland law, they are de facto illegal. There have been cases where courts have disallowed VIEs. But historically, the state has never formally clarified their legitimacy. Therefore there was a risk that VIEs could be declared void, wiping out foreign investment in these issuers overnight.

Over the years, it seemed as if the Mainland would clarify its stance. For example, in the first draft of the Foreign Investment Law issued by the Ministry of Commerce in 2015, the authorities proposed to address the VIE issue by making sure the controlling shareholders of these structures were Chinese nationals. However, this proposal raised various concerns among market participants, particularly how to reverse-engineer companies like Tencent with its largest shareholder being Naspers, a South Africa–based company.

The trade war between the US and the Mainland from 2018 served as a further distraction for the Mainland government in solving this issue. In the final version of the Foreign Investment Law published in 2019, the VIE issue was not mentioned at all.

What do US regulators make of VIEs?

Over the past two decades, both the US and the Mainland seemed to have given tacit approval for the structure by steering clear of this grey area. When the Mainland launched the new tech board under the Shanghai Stock Exchange in 2019, the regulator allowed VIEs to list on the bourse and treated them the same as other issuers. Such a ‘silent strategy’ significantly benefited both international investors and the Chinese private sector.

But the silence was broken by US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) chairman Gary Gensler in July 2021 when he talked about ‘offshore shell companies’ in a speech. It was seen as a response to the PRC government’s further restrictions on Mainland-based companies seeking overseas listings amid data security concerns. The regulator has since then stopped processing IPO applications from Chinese companies. On 2 December 2021, Gensler also warned that Chinese companies would not be allowed to raise money in the US and would be delisted in three years unless they allowed audit inspections by the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board.

This development proved to be a shock to many investors, judging by the share performance of many US-listed Chinese companies in 2021. But many of these companies disclosed their exposure to such risk in their IPO prospectuses. For example, Alibaba clearly stated in its F-1 filing back in 2014:

‘If the PRC government deems that the contractual arrangements in relation to our variable interest entities do not comply with PRC governmental restrictions on foreign investment, or if these regulations or the interpretation of existing regulations changes in the future, we could be subject to penalties or be forced to relinquish our interests in those operations.’

The China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) released draft rules on 23 December 2021 to increase oversight of Mainland companies listing overseas, including those using VIEs. It seems to now be saying companies can still use the VIE structure for overseas listings. Is that right?

Yes, the CSRC has recently said in several public speeches that they had no intention of banning companies, including those with the VIE structure, from overseas listings. The consultations published by the CSRC in December put an emphasis on companies making proper registration with the regulators so that they can effectively monitor the listing status of the applicants.

It is not beneficial to the Mainland economy to curb foreign financing of Chinese companies, especially privately owned ones, and the government knows this. There has been no major lowering of hurdles for companies to obtain domestic finance over the past two decades, so Chinese companies rely on this pipeline to maintain long-term growth.

What kind of companies would be likely to still use a VIE structure to list overseas?

The same types of companies will continue to use VIEs, but private firms in the technology and education sectors, as well as others which are restricted by the authorities, are more limited in their ability to directly list overseas. And as both the Mainland and the US tighten up rules on Chinese companies listing in New York, I think it will be challenging for a Mainland company with a VIE structure to raise capital overseas.

In was reported in December 2021 that Mainland authorities, including the state planner, commerce ministry, securities regulator and central bank, were preparing a blacklist which would closely confine the main channel used by private PRC firms to attract global funds and list overseas. The blacklist will target new companies in sensitive sectors that raise data or national security concerns. The move is aimed at limiting the role of foreign capital in the Mainland’s next generation of tech giants, but is not expected to affect existing VIEs.

For companies already listed overseas with VIE structures, what do you think the draft rules will mean in practice?

The CSRC has said that the rules shall not have a retrospective effect, so companies with existing VIE structures should not be affected. The regulator has also said that a Hong Kong listing does not count as an overseas listing in this respect.

The tricky question is how both Mainland and US regulators will deal with existing VIEs. The Mainland has been asking companies to transfer their databases to state-owned entities or to allow government access to their critical intellectual properties (gaining board seats, integrating systems and so on). On the other hand, the SEC issued disclosure guidance on December 20 to ask US-listed Chinese companies to provide more information on their use of VIEs. It will be interesting to see how these companies will disclose VIE-related risks in their next annual reports.

Do you think the CSRC’s decision not to ban VIE structures, and instead to tolerate them, will make any difference to the way the US regulators view VIEs?

No. I think Gary Gensler’s speech in July 2021 demonstrated that the US is on a clear path. Having said that, I doubt it took the SEC 20 years to realise how poorly investors’ interests were protected under this structure. I think on this issue the US regulators are being driven by a combination of market supervision issues, geopolitics and business concerns, hence the decision for the US to take action over the past two years.

Will Hong Kong see an influx of Mainland companies delisting from the US and choosing to list here?

DiDi Chuxing (Didi) already announced on 3 December 2021 that it was delisting from the New York Stock Exchange and would choose Hong Kong as a ‘homecoming’ listing. It had not even been half a year since the company chose New York over Hong Kong to perform its US$4.4 billion IPO. Such a retreat so soon after listing is taking a toll on Didi’s shares – the stock fell from the IPO price of US$14 to less than US$5 in late January 2022.

Our contacts close to the CSRC have told us that the regulator had no intention of limiting opportunities for companies with a VIE structure to list in Hong Kong. Taking the hint, US-listed Mainland tech giants such as Alibaba, JD.com, Baidu, NetEase and Weibo have already performed a secondary listing in Hong Kong in recent years.

Is this a windfall for Hong Kong? Those who look at it merely through a fundraising lens may think so. But ACGA is concerned with some of the hallmark attributes of these ‘new economy’ stocks, such as their dual-class share structures, low ESG scores and, more importantly, the decision by founders of some of the Mainland’s biggest tech giants to formally relinquish their leadership roles. You could equally argue that Hong Kong runs the risk of becoming a landfill for poorly governed US-listed Chinese companies in the near term.

Nana Li, Research and Project Director, China

ACGA

© Copyright January 2022 ACGA

This article first appeared as a blog on ACGA’s website on 25 January 2022. For further details about ACGA, please visit www.acga-asia.org.