Modernising Chinese antitrust – What’s to come from the amended Anti-Monopoly Law

Natalie Yeung, Partner, Alexander Lee, Counsel, and Michele Ho, Associate, of Slaughter and May, explain the recent amendments to the Mainland’s Anti-Monopoly Law and examine the implications of these changes for Chinese antitrust enforcement.

Change is coming to antitrust law in the Mainland. After over two years of consideration and consultation, the Chinese legislature recently passed its first amendment to the Anti-Monopoly Law (AML), with changes ranging from an updated merger control regime to new substantive rules and safe harbours governing anti-competitive conduct, and enhanced sanctions across the board. Corresponding updates to detailed antitrust and merger regulations were published for consultation shortly after the revised legislation was passed. We take a brief look at what these changes mean for Chinese antitrust enforcement going forward.

Key changes coming to Chinese antitrust

The AML revisions were approved by the Standing Committee of the 13th National People’s Congress on 24 June 2022, making this the country’s biggest effort to modernise its antitrust regime to date. The AML’s legislative amendments, which took effect on the law’s 14th enforcement anniversary on 1 August 2022, come as no surprise to antitrust practitioners, as they are broadly in line with the proposed amendments published during previous consultations since January 2020.

Proposals to update antitrust and merger regulations came hard on the heels of the AML amendments, as the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) published six draft regulations for public consultation on 27 June 2022, covering revisions to its existing regulations on anti-competitive (monopolistic) conduct, abuse of market dominance, abuse of intellectual property rights, merger control thresholds (Draft Merger Thresholds Regulation) and review, and abuse of administrative power (collectively, Draft Regulations). Consultation on the Draft Regulations ended on 27 July 2022.

Here are the key changes:

China merger control 2.0

The amended AML and Draft Regulations seek to introduce a number of changes that will bring fundamental change to the existing merger control regime, including: 1. Higher jurisdictional thresholds. With a view to better capture transactions that merit review, SAMR is proposing in the Draft Merger Thresholds Regulation to increase filing thresholds to:

- the parties having a combined worldwide turnover exceeding RMB12 billion (approximately US$1.8 billion), or Chinese turnover exceeding RMB4 billion (approximately US$600 million), in the preceding financial year, and

- at least two parties each having Chinese turnover exceeding RMB800 million (approximately US$120 million), which is double the current Chinese turnover requirement of RMB400 million.

2. A catch-all power for ‘killer acquisitions’. The amended AML now enshrines SAMR’s power to call in transactions that fall below turnover thresholds. In addition, the Draft Merger Thresholds Regulation envisages a special merger notification requirement for businesses whose Chinese turnover exceeds RMB100 billion (approximately US$15 billion), and the other party’s market value (note: not turnover) exceeds RMB800 million (approximately US$120 million) if its Chinese turnover represents more than a third of its global turnover. This catch-all power is expected to capture killer acquisitions, for example, market incumbents acquiring a nascent rival to stifle future competition.

3. New ‘stop-the-clock’ mechanism. SAMR will have the power to suspend the merger review period by written notice in circumstances where more time is needed (such as when a deadline to provide requested information is not met, or new material facts require verification). Notifying parties may also apply to suspend the review process to allow time for remedy discussions. With this power, SAMR may no longer need to ask parties to ‘pull and refile’ complex notifications in order to allow more time to discuss remedies, but it also gives rise to a risk that SAMR could issue requests for information just to buy itself more time to review the transaction.

4. A ‘classification and grading’ system. While details of this system are yet to be announced, the new system is expected to allow SAMR to triage merger filings for better administration and resource allocation, possibly on the basis of sector-specific filing thresholds. SAMR launched a three-year pilot programme on 1 August 2022 to delegate simple cases with a local nexus to its provincial or local branches in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong, Chongqing and Shaanxi. The delegated agencies will be responsible for reviewing assigned cases, whereas SAMR will supervise such reviews and decide on the outcome of such cases.

Refinements on substantive rules

The revisions to the AML include a number of additions that bring the Chinese rules more into line with international standards of competition enforcement.

1. Safe harbours for vertical agreements. The amended AML introduces, for the first time, a general safe harbour for all vertical agreements, provided no harm to competition would arise from the vertical restriction, and the market shares of relevant parties fall under a specified threshold. Currently, SAMR is proposing a 15% market share threshold for this safe harbour for vertical agreements under the Draft Regulation on the Prohibition of Monopolistic Agreements.

2. Rebuttable presumption of illegality for resale price maintenance (RPM). While RPM is expressly prohibited under the original AML, the amended AML specifies that RPM may not be illegal if parties can prove that the restriction does not harm competition – although the difficulty of discharging this burden remains unclear. This is nevertheless a notable change, as SAMR and its provincial/local branches have in the past appeared to prioritise enforcement against RPM on a ‘per se’ basis. Businesses would therefore be prudent to wait and see, and to seek legal advice before implementing RPM in their supply or distribution agreements in the Mainland, even if they consider there are good arguments that this would not harm competition.

3. Express liability for facilitators of anti-competitive agreements. The amended AML includes a new prohibition on organising or assisting others to reach anti-competitive agreements. This is expected to cover all indirect forms of collusion, including hub-and-spoke cartels. Liability under this prohibition will be imposed on a standalone basis, meaning the facilitator to collusive arrangements will be sanctioned as though it were a member of the cartel in question.

4. Tailored rules for the digital economy. Big tech is a notable theme that stands out among the many changes to the AML. In particular, ‘the use of data, algorithms, technologies, capital advantage and platform rules’ are now specified as potential means of infringing the prohibitions against anti-competitive agreements and abuse of market dominance. The flexible language leaves the door open for Chinese authorities to scrutinise future variants of anti-competitive conduct as new technology or business models emerge.

Harsher sanctions for AML infringements

Deterrence under the amended AML will be significantly higher, as penalties for all aspects of AML infringements are increased.

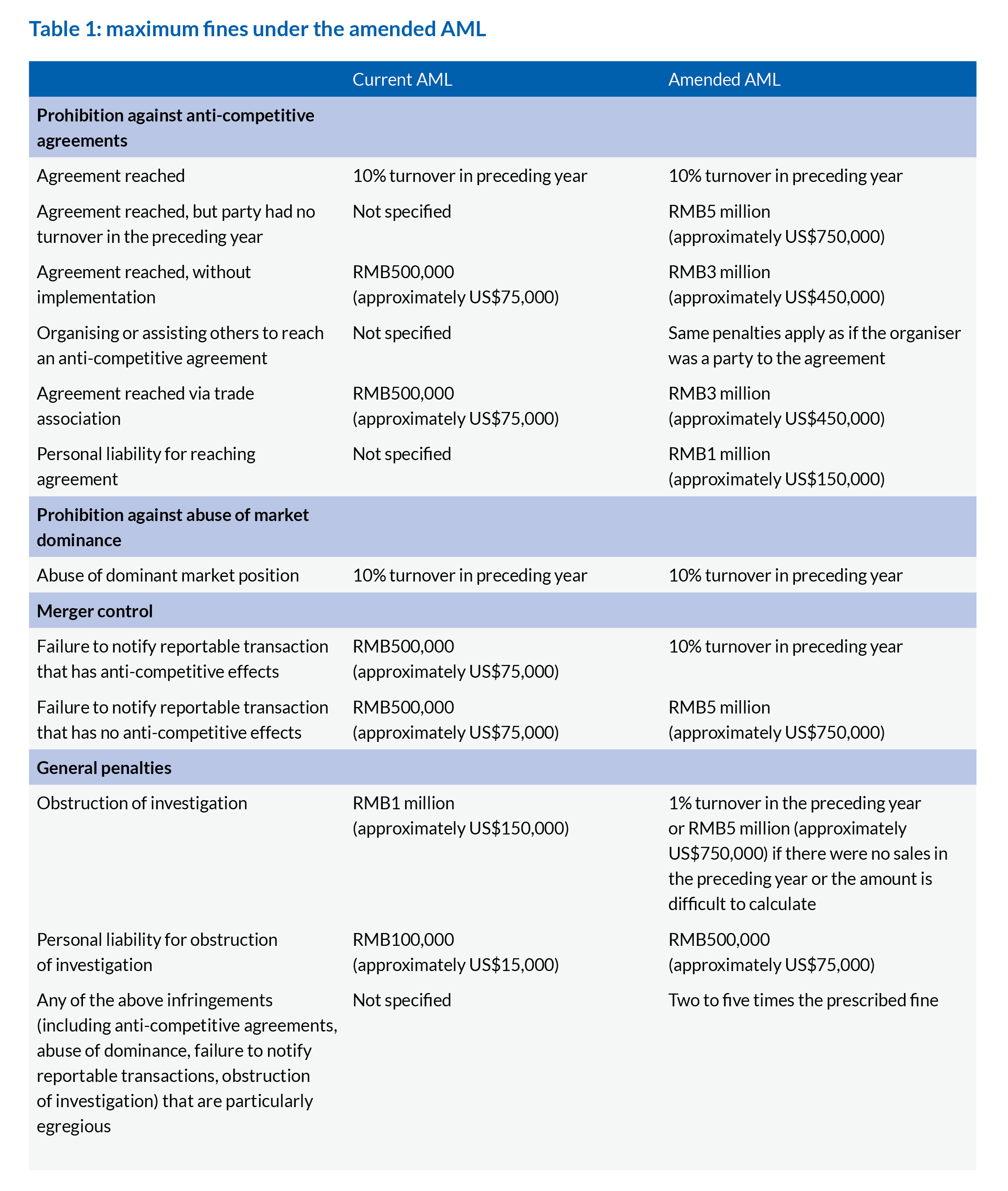

1. Higher fines for antitrust violations, particularly for gun-jumping. The maximum fine for a failure to notify a reportable transaction will see the highest jump in penalty: from the current cap of RMB500,000 (approximately US$75,000) to 10% of turnover in the preceding year if the deal has anti-competitive effects, or RMB5 million (approximately US$750,000) for other cases. A new ‘two to five times penalty multiplier’ has also been introduced for particularly egregious antitrust violations. See Table 1 for a summary of the potential fines under the amended AML.

2. Personal accountability for AML infringements. Individuals in charge of Chinese businesses (such as legal representatives or company directors) or individuals directly responsible for the company’s anti-competitive agreement may find themselves personally subject to a fine up to RMB1 million (approximately US$150,000). Personal pecuniary penalties for obstruction of AML investigations have also been raised substantially from the current cap of RMB100,000 to RMB500,000 (approximately US$75,000).

3. Corporate social credit record for AML. Administration penalties for AML violations will be kept on the company’s social credit record. As China’s social credit record system is public, this may have a reputational impact on businesses that violate the AML.

4. Civil recourse via public interest litigation. Businesses found to have breached the AML may also be subject to public interest civil lawsuits (similar to class-action litigation) brought about by the People’s Procuratorate (public prosecutorial bodies in China).

A new era of antitrust enforcement

There are many welcomed changes in the amended AML. The revamped merger control regime is expected to allow better case management, while capturing transactions that more likely merit SAMR’s review (for example, killer acquisitions). However, it also introduces a certain degree of uncertainty and we will have to see how SAMR exercises its new powers in practice. The additional guidance on substantive antitrust rules and safe harbour for vertical agreements affords greater legal certainty for businesses operating in the Mainland. The rules specifically tailored for the digital economy add a layer of future-proofing to the AML. Together, the amendments bring the Chinese antitrust regime closer to international equivalents and are expected to strengthen antitrust enforcement with greater fines.

Businesses should note that proposals under the Draft Regulations may be subject to SAMR’s fine-tuning, depending on comments received during the consultation. The revised Regulations have yet to be published as of the date of writing, but such revisions are expected to be published in the near future, so as to align with the AML amendments that came into effect on 1 August 2022.

Natalie Yeung, Partner, Alexander Lee, Counsel, and Michele Ho, Associate

Slaughter and May

© Copyright July 2022 Slaughter and May