Dr Agnes KY Tai, Director, Great Glory Investment Corporation, shares the findings of her 2022 PhD research, looking at how investors respond to the carbon risks and environmental performance of Hong Kong listed companies.

2022 was a year of more than 500 catastrophic weather events that tallied to a global cost of US$270 billion. Heatwaves such as Greenland’s temperature at 8°C warmer than average, wildfires that raced across Spain, droughts in various parts of Europe that were the worst in 500 years, along with prolonged droughts in Africa, floods in Pakistan that affected over 33 million people and displaced 8 million, and alarmingly low sea ice level at the Arctic and Antarctica, are all daunting signs that climate risks due to global warming are here now, not in 2100.

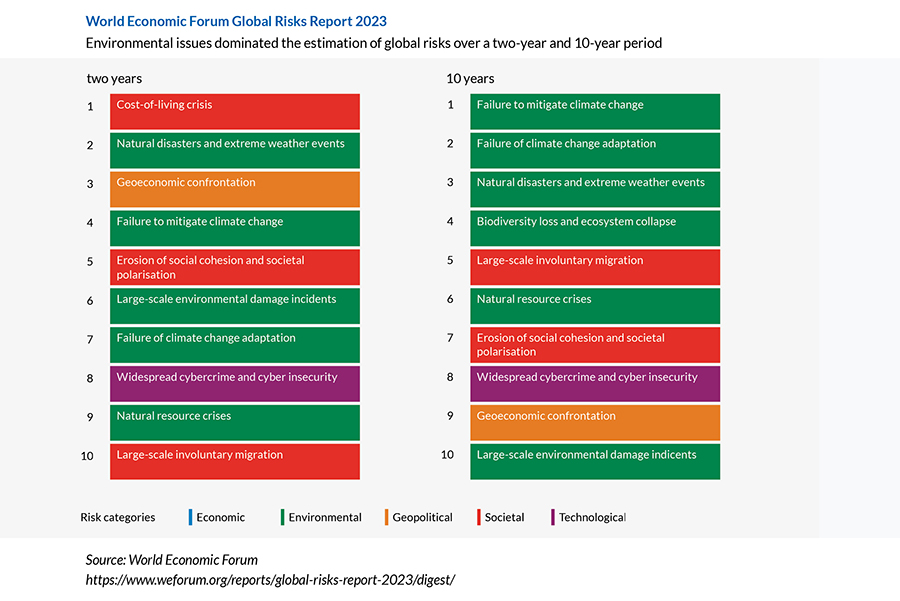

The World Economic Forum Global Risks Report 2023 shows six out of 10, in the 10-year horizon, as climate and environmentally related. Scientists using an AI model predict a nearly 70% chance of the world crossing the two-degree threshold between 2044 and 2065. Climate inaction could cost the global economy US$178 trillion over the next 50 years, according to a Deloitte report (Path to Economic Disaster: Climate Inaction Could Cost $178 Trillion by 2070, published 25 May 2022).

The Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures categorises climate risks into:

1. physical risks – acute (such as fires, droughts, floods and hurricanes), and chronic (such as heat, precipitation and rising sea levels), and

2. transition risks – comprising policy and legal, technology, market and reputation,

where each can impact a firm financially. Carbon risks of firms pertain to financial impact associated with climate transition risks.

Active decarbonisation of investment and lending portfolios

Not only do businesses suffer supply shortages, power failures, business disruptions, facilities repair costs, reduced worker productivity and higher insurance premiums in the face of physical climate risks, their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions could lead to costly transition risks if not genuinely abated.

Global investors, financiers, customers, employees and non-profit organisations are scrutinising the GHG reduction commitments of companies, partly due to regulatory pressure on them to decarbonise their investment or lending portfolios. The reason behind the push to decarbonise is that carbon risks will impair the growth of their portfolio companies. Potential asset write-downs or write-offs, new carbon taxes or fines, higher cost of capital and capital expenditure, and a drain on cash flow all translate to lower enterprise valuations and/or higher risks of debt default in their portfolio companies.

Demands from regulators and capital providers

Carbon risks are not taken lightly. Corporate board directors are being held accountable for climate governance. They are expected to have sufficient knowledge in the ‘double materiality’ of climate risks (how climate impacts the business financially, and how the firm’s GHG emissions affect the planet and society), and to commit to a credible plan for reducing emissions and improving transparency in disclosures. Shareholder activism and court actions are on the rise.

In May 2021, Engine No 1 was successful in replacing three (out of 12) board directors of Exxon Mobil via AGM voting to push the energy giant to reduce its carbon footprint.

Although owning 0.02% of Exxon’s shares, they were backed by large pension funds, including CalPERS, calSTRS and the New York State Common Retirement Fund. The world’s top three asset managers BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street also voted against Exxon’s leadership.

On 9 February 2023, ClientEarth filed a lawsuit against 11 board directors of Shell plc for inadequate climate strategy that would put the oil giant at financial risk. The environmental legal firm’s court action was supported by large pension funds such as UK’s Nest and London CIV, and asset managers like Sanso IS and Danske Bank Asset Management. In May 2021, Friends of the Earth and more than 17,000 co-plaintiffs succeeded in a landmark case against Shell, whereby a Dutch court ordered the company to reduce CO2 emissions from its products by 45% by 2030. Shell is appealing.

The largest global sovereign wealth fund of Norway announced in 2017 that it will divest 20% of the country’s portfolio from oil and gas. In early February 2023, this large asset owner warned company directors that it will vote against their re-election to the board if they do not take serious action on climate change, human rights abuses and boardroom diversity.

In October 2021, AIA Group, the largest pan-Asian insurance firm, announced that it had divested from listed coal mining and coal-fired power businesses in its self-managed equity and fixed income investments, seven years ahead of its original divestment strategy goals. The Group has committed to achieving net-zero GHG emissions by 2050, as have over 550 financial institutions from over 50 jurisdictions that have joined the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ).

Can carbon offsets reduce carbon risks?

Business leaders are increasingly aware of the risks and opportunities presented by climate change. In response to demands from capital providers, regulators and civic society, and to be a responsible corporate citizen, companies are making ambitious commitments to achieve net zero in their operations and products/services by a future year, mostly 2050.

Renewable energy costs have fallen in the past decade, so much so that they are highly competitive. The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) reported that in 2021 almost two-thirds of renewable power had lower cost than the cheapest coal-fired options in G20 countries. However, not every business has access to renewable energy and GHG emissions for 2022 reached 58 gigatons (GT). To achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, emissions have to fall by three GT each year for the next three decades, instead of an annual increase of 6% as in the recent past.

With a growing population and economic growth, no meaningful GHG emissions reduction is achievable when affordable carbon capture and storage technology at scale is not available. A number of companies in Europe, California in the US, the Mainland and other jurisdictions are subject to a compliance emissions trading system where they are to purchase carbon credits when GHG emissions exceed assigned thresholds. Some companies that pledged to achieve net-zero have resorted to voluntary purchases of carbon credits in the carbon exchanges to ‘offset’ hard to abate carbon emissions. Core Climate, launched by Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Ltd (HKEX) in October 2022, is an example of a voluntary carbon exchange that also operates a registry.

Large capital providers engage with high GHG emitting companies to support them in a credible reduction plan, and in doing everything within their capacity to reduce GHG emissions before purchasing quality carbon credits to offset residual carbon emissions. Quality carbon credits have the characteristics of additionality, permanence and measurability, and are verified by a recognised standards body and registered. Without additionality, real decarbonisation of the global economy is questionable or even unachievable.

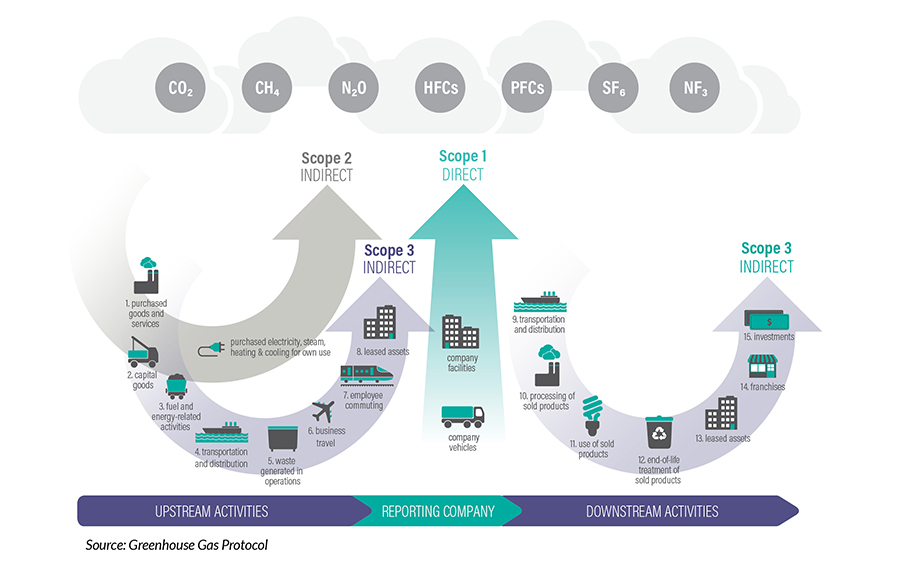

Scope 3 carbon emissions are referred to as ‘portfolio emissions’ for asset owners and managers, and ‘financed emissions’ for banks. The Net Zero Asset Owners Alliance, with members controlling US$11 trillion in assets, announced in January 2023 that members are banned from counting carbon offsets toward their carbon reductions, so that members take real action in reducing their carbon footprint. The effect of this ban will trickle down to asset managers and to portfolio companies over time, but its impact will likely be felt soon.

Do carbon risks matter for Hong Kong equity prices?

Over 40% of companies listed on HKEX have Mainland backgrounds or operations, making up around 60% of the total market capitalisation. For the other 60%, many large listed firms are majority-family-held. Institutional investors are active in the Hong Kong stock market, and they deploy investment criteria and methodology here as in other developed capital markets.

In 2022, I completed my PhD research titled Do Carbon Risks Matter for Hong Kong Equity Prices? The research contributes to several knowledge gaps by being the first to study the impact of investors’ perception of carbon risks on Hong Kong listed equity prices. This study also uncovered investors’ motivation. The use of mixed methods – regression analysis and expert elicitation (interviews) – and novel carbon risk proxies are additional contributions of this behavioural finance study. Overall, both regressions and interview results show that investors are more inclined to penalise Hong Kong listed companies that are environmental laggards, rather than reward less carbon intensive ones. Not only do global institutional investors care about carbon risks, but they also respond by penalising companies with poor environmental performance, resulting in a discount to their share prices.

Interviews with selected global institutional investors, who collectively have over US$19 trillion in assets under management, suggest that most of them are concerned about companies’ poor environmental performance and the damage this causes to their long-term financial prospects. Interview results further emphasise that ESG (environment, social and governance) concerns are viewed holistically, and the ‘E’ pillar is important for sectors where it is material. Respondents also expect environmental performance to impact corporate financial performance significantly in the long run, despite having little effect in the short and the medium term. ESG alone does not overshadow return on investment, which is considered as the institutional investors’ first and foremost fiduciary duty.

88% of the capital providers represented in the interview panel showed willingness to pay a premium for good environmental performance. More importantly, over 90% of them will likely divest stocks with persistently poor environmental performance or exclude them from their investible universe, the severest action that investors can deploy.

The findings can guide global investors in:

- making informed decisions when they are mandated to include Hong Kong listed companies in their portfolios

- making investment decisions

- deploying resources in research and corporate engagement

- regulatory reporting, and

- communicating with clients.

Understanding how investors respond to the carbon risks and environmental performance of Hong Kong listed companies can help corporates strategise and communicate better with their stakeholders.

HKEX, the Securities and Futures Commission and the Hong Kong Monetary Authority can use the findings to structure their policies to ensure the continued integrity of the markets, and to strengthen Hong Kong’s position as a regional and Greater Bay Area green finance hub, as well as its world standing as an international financial centre. Service providers can use the findings of this study to educate investors and corporates about the need to better manage their carbon risks, as well as to communicate such risks to them proficiently.

How can your business adopt actionable climate strategies?

Understanding both physical and transition risks and their opportunities; how the (non-linear) risks impact the business financially and over what time horizon; setting ambitious yet achievable emissions reduction targets; balancing climate investments with financial performance; sticking with the plans; and being transparent with reporting are elements of good climate governance practices. Often, a sustainability committee at the board or management level is necessary to coordinate the complex issues. Having an open and forward-looking mindset is another key attribute.

To counter climate physical risks, a company should adopt adaptation strategies to ensure resilience over a long time period. To tackle climate transition risks, having a quality dataset also covering Scope 3 emissions (including those of suppliers, customers and portfolio companies) and internal carbon pricing are some good starting points. Before engaging external consultants, seek best practice examples from investors, banks and industry associations. Resources are not unlimited and effective deployment towards strategic choices require careful consideration.

With prompt meaningful climate action, future generations will be better off, and businesses can be supported by sustainability-aligned investors to stay on a sustainable growth path.

Dr Agnes KY Tai, Director

Great Glory Investment Corporation

The author is also Head of Sustainability Investment and Advisory, Asset Management, of Arta TechFin Corporation Ltd, a Council member of the Hong Kong Institute of Directors and a Steering Committee member of Climate Governance Initiative Hong Kong Chapter. She has authored a book on investing in H shares, a Harvard Business case and a positive psychology book Tall Miracles.